UNIT #3 What Is The Most Concerning?

"What to do While You Wait, Investigate!" ~ Prioritize Concerns, with < My Thoughts > by Sara Luker

Parents often must wait days, weeks, and even months for assessments or doctor appointments. During this stressful time, it's good to feel that you are actively helping your child. This can become an important time of clarifying what bothers you the most about your child's behavior, development, or other concerns. Video tape what you are seeing and how your child acts throughout the day/night. 'Seeing is believing' for someone new to your child.

Prioritize your child's 'needs' and your 'wants'. Try new things... like teaching your child age appropriate 'developmental skills' that are non-invasive. See what works and what doesn't. Eventually, you will have to choose from available programs, therapies, and services that will be offered. Some are quite expensive, so understand your child well enough to figure out what will probably work and what absolutely won't. You can only know this by trying some things on your own.

NOTE about: “Programs, Therapies, & Interventions”

Information about INTERVENTIONS, THERAPIES, PROGRAMS, and/or TREATMENTS is presented without intent or suggestion of status or effectiveness; or even with the title of an autism ‘intervention’. Most places in the literature and even in some laws, the word ‘intervention’ is used interchangeably with ‘instructional/educational program’, ‘therapy’, and ‘treatment’. The very word ‘INTERVENTION’ when used in the same sentence with ‘autism’ may imply ‘cure’ or ‘long-term’ effect. That is NOT the intention here.

Autism ‘intervention’ as with the phrase, “Early Detection / Early Intervention” may simply mean an ‘action’, or an attempt to ‘change a course’ or trajectory of autism. Also, the expectation for success is that all ‘interventions/therapies/programs will have the cooperation of the participant, the parent, and/or the assigned therapist.

There are many different types of treatment programs, interventions, and services being tried by parents and schools. Also, your child’s challenges may require having several non-competing therapies at once. Therefore, carefully consider the cost and time involved for your child and your family. Be very careful to fully understand your obligations. To some, AUTISM is a business. So, remember that gym/spa membership you paid for every month for three years, even though you only went there a few times? You could find yourself in the same type of situation here.

Disclaimer: Just to let you know that I, Sara Luker, have put forth my best efforts to create the extended book reviews presented here on this website. I have permission from the authors to publish these Extended Book Reviews. This is just a sharing of stories of those who have gone on before us. Please, understand also that all health matters ALWAYS require professional medical decisions, diagnosis, and treatment by highly qualified and licensed individuals.

Regards,

Sara Luker

"What to do While You Wait, Investigate!" ~ Prioritize Concerns, with < My Thoughts > by Sara Luker

Parents often must wait days, weeks, and even months for assessments or doctor appointments. During this stressful time, it's good to feel that you are actively helping your child. This can become an important time of clarifying what bothers you the most about your child's behavior, development, or other concerns. Video tape what you are seeing and how your child acts throughout the day/night. 'Seeing is believing' for someone new to your child.

Prioritize your child's 'needs' and your 'wants'. Try new things... like teaching your child age appropriate 'developmental skills' that are non-invasive. See what works and what doesn't. Eventually, you will have to choose from available programs, therapies, and services that will be offered. Some are quite expensive, so understand your child well enough to figure out what will probably work and what absolutely won't. You can only know this by trying some things on your own.

NOTE about: “Programs, Therapies, & Interventions”

Information about INTERVENTIONS, THERAPIES, PROGRAMS, and/or TREATMENTS is presented without intent or suggestion of status or effectiveness; or even with the title of an autism ‘intervention’. Most places in the literature and even in some laws, the word ‘intervention’ is used interchangeably with ‘instructional/educational program’, ‘therapy’, and ‘treatment’. The very word ‘INTERVENTION’ when used in the same sentence with ‘autism’ may imply ‘cure’ or ‘long-term’ effect. That is NOT the intention here.

Autism ‘intervention’ as with the phrase, “Early Detection / Early Intervention” may simply mean an ‘action’, or an attempt to ‘change a course’ or trajectory of autism. Also, the expectation for success is that all ‘interventions/therapies/programs will have the cooperation of the participant, the parent, and/or the assigned therapist.

There are many different types of treatment programs, interventions, and services being tried by parents and schools. Also, your child’s challenges may require having several non-competing therapies at once. Therefore, carefully consider the cost and time involved for your child and your family. Be very careful to fully understand your obligations. To some, AUTISM is a business. So, remember that gym/spa membership you paid for every month for three years, even though you only went there a few times? You could find yourself in the same type of situation here.

Disclaimer: Just to let you know that I, Sara Luker, have put forth my best efforts to create the extended book reviews presented here on this website. I have permission from the authors to publish these Extended Book Reviews. This is just a sharing of stories of those who have gone on before us. Please, understand also that all health matters ALWAYS require professional medical decisions, diagnosis, and treatment by highly qualified and licensed individuals.

Regards,

Sara Luker

WHAT IS MOST CONCERNING?

INTRODUCTION

Chapter 1 – Gross & Fine Motor Skills (Including

‘proprioception’)

PART 1 – Poor Eating

PART 2 – Toilet Training

APPENDIX A – Toileting

PLEASE READ DISCLAIMER

INTRODUCTION

Chapter 1 – Gross & Fine Motor Skills (Including

‘proprioception’)

PART 1 – Poor Eating

PART 2 – Toilet Training

APPENDIX A – Toileting

PLEASE READ DISCLAIMER

UNIT 3 – WHAT IS MOST CONCERNING?

INTRODUCTION

What is the most concerning thing that is going on right now in your child’s world? Be honest about what you are seeing. Try to document when and where ‘it’ happens. You may be seeing a very mild ‘sometimes’ behavior, but it’s still concerning to you. Or, ‘it’ may be a dangerous and truly distressing; or ‘somewhere-in-between’ behavior. Document ‘it’, even if you just use coded hash mark on a calendar, or record on your phone.

One way to try to figure out the ‘function’ or purpose of the behavior is by determining what has happened ‘just before’ the unwanted behavior. Identifying the ‘trigger’ aka the ‘antecedent’, may be helpful in avoiding future scenarios. But also know that you may not immediately figure know what that trigger is. Especially if it turns out to be ‘sensory’ issues, then the trigger may have happened hours ago.

< My Thoughts > “…future scenarios.”

For instance, if we’ve been trying to give Sonny homemade protein loaf for snacks instead of packaged cookies, I avoid taking him down the cookie aisle in the grocery store. He is someone who is easily ‘visually’ stimulated, so who can blame him if the sight of an endcap of Oreos is just more than he can handle? If seeing all those cookies puts him on sensory overload, especially if he feels temporarily deprived, then a kicking and screaming tantrum, or even a meltdown is certain.

Hus & Lord (2013), tell us the “differences in autism presentation are striking.” Some children with autism can start experiencing greater differences in the degree of their condition or disorder, as time goes on. The differences can change too, with more emphasis on, or addition of sensory disorders, sleep disorders, gastrointestinal tract disorders, epilepsy, or learning and language delays.

Document concerning behaviors such as – ‘tantrumming’, and ‘I want it and I want it now’ behaviors, and ‘sensory meltdowns’. Note, that meltdowns are NOT usually a ‘thought-out’ behavior but a likely ‘sensory’ reaction. While these behaviors are high on the list of parental concerns, recent studies show the following things also worry parents.

Lack of age-typical development of –

These ‘concerns’ will just be addressed in the order in which they appear, NOT in any other implied order.

NOTE: ‘BEHAVIOR’ is not addressed as a separate topic, but appears throughout the chapters as a ‘response’ to the environment. Behavior tells us how the child is reacting to his or her world. Or, what is physically happening within their body which may be provoking the unwanted ‘behavioral/response’.

INTRODUCTION

What is the most concerning thing that is going on right now in your child’s world? Be honest about what you are seeing. Try to document when and where ‘it’ happens. You may be seeing a very mild ‘sometimes’ behavior, but it’s still concerning to you. Or, ‘it’ may be a dangerous and truly distressing; or ‘somewhere-in-between’ behavior. Document ‘it’, even if you just use coded hash mark on a calendar, or record on your phone.

One way to try to figure out the ‘function’ or purpose of the behavior is by determining what has happened ‘just before’ the unwanted behavior. Identifying the ‘trigger’ aka the ‘antecedent’, may be helpful in avoiding future scenarios. But also know that you may not immediately figure know what that trigger is. Especially if it turns out to be ‘sensory’ issues, then the trigger may have happened hours ago.

< My Thoughts > “…future scenarios.”

For instance, if we’ve been trying to give Sonny homemade protein loaf for snacks instead of packaged cookies, I avoid taking him down the cookie aisle in the grocery store. He is someone who is easily ‘visually’ stimulated, so who can blame him if the sight of an endcap of Oreos is just more than he can handle? If seeing all those cookies puts him on sensory overload, especially if he feels temporarily deprived, then a kicking and screaming tantrum, or even a meltdown is certain.

Hus & Lord (2013), tell us the “differences in autism presentation are striking.” Some children with autism can start experiencing greater differences in the degree of their condition or disorder, as time goes on. The differences can change too, with more emphasis on, or addition of sensory disorders, sleep disorders, gastrointestinal tract disorders, epilepsy, or learning and language delays.

Document concerning behaviors such as – ‘tantrumming’, and ‘I want it and I want it now’ behaviors, and ‘sensory meltdowns’. Note, that meltdowns are NOT usually a ‘thought-out’ behavior but a likely ‘sensory’ reaction. While these behaviors are high on the list of parental concerns, recent studies show the following things also worry parents.

Lack of age-typical development of –

- gross/fine motor skills (Ch. 1; including ‘eating & toileting’)

- speech/language communication (Ch. 2; including ‘non-verbal’)

- cognition, temperament/personality expression

- social/personal awareness

- daily living skills

These ‘concerns’ will just be addressed in the order in which they appear, NOT in any other implied order.

NOTE: ‘BEHAVIOR’ is not addressed as a separate topic, but appears throughout the chapters as a ‘response’ to the environment. Behavior tells us how the child is reacting to his or her world. Or, what is physically happening within their body which may be provoking the unwanted ‘behavioral/response’.

CHAPTER 1 – GROSS & FINE MOTOR SKILLS (Including ‘proprioception’)

Depending on the age of the child, probably the fact that s/he may not be meeting their 'developmental milestones' could be due to poor motor skills. Both 'gross' (using large muscles involving walking and/or easily moving the body) and 'fine' (involving pincer and/or grasping skills) should be developing as expected. But if they are NOT developing typically, that may be because motor skill deficits are affecting the child’s necessary mobility, keeping them from becoming their best ‘independent’ selves.

Menear, et al. (2006) tell us that their informal observations have shown that many students with autism who have ‘low’ motor skills and few fitness abilities will have initial difficulty in traversing typical school or park playground equipment without assistance. Poor eye-hand coordination, trouble combining multiple motor skills into one task, and any structured balance related physical activities, as well as participating in group activities can be difficult.

< My Thoughts > “…motor skills and few fitness abilities…”

What to do while you wait for doctors, diagnosis, and direction? Try teaching activities which develop ‘gross/large’ motor skills. This can be done with your child while you are ‘waiting’ for the ‘new’ world of doctor’s appointments, consultations, final diagnosis, and program possibilities to open up for you.

Autism related tiptoeing, clumsiness and tripping on stairs may be occasional and even subtle, but when it happens often enough then it can become a safety issue. And, added to other core symptoms may be about autism.

You might try two types of physical programs – aerobic and aquatic. Both can be ‘fun’ activities you can do with your child and/or find in your local area. Look for 'Challenger' or 'Adaptive' and ‘Alternative’ programs offered by community organizations. You don’t have to have the child’s ‘diagnoses’ to participate in most community adaptive/alternative activities. Plus, you may meet new friends there and possibly do important networking.

Note: More about ‘Networking’ in UNIT 6, Ch. 1.

Morin (2017) cautions that children’s preferences change over time. As your child ages, peers and other adults will encourage the pursuit of new interests. It's normal for a child to want to play different sports, hear new types of music and engage in new artistic activities.

< My Thoughts > “…pursuit of new interests.”

The ‘normally developing’ child eventually becomes interested in what others are doing. A child on the autistic spectrum seems mostly to be ‘self-involved’ with ‘preferred activities; lining-up toys, watching the same video repeatedly, and/or traveling the same paths over-and-over.

While getting to know your child, help to pursue new interests, understand his/her ‘fine / gross’ motor skills, and ‘fitness abilities’.

Parents may want to try ‘tying’ a new activity to a favorite one. For instance, Sonny loves to walk on our garden path; stopping to visit certain flowers, or ceramic frogs. We find ways to add new interests by stopping to sit on a bench to listen to a brief moment of music on a MP3 Player.

In another setting, a therapist suggested that we add a very short clip from a National Geographic show to the end of the ‘Blues Clues’ recording; which Sonny watches on a loop. At first, the added documentary clip about polar bears seemed to annoy him, but eventually he settled down and watched it. Mission accomplished!

Be cautious but unafraid. Work with your child to allow experimentation and growth. Over time, you will come up with additional safe, appropriate, and positive types of activities. Know also, that many ‘activities’ are resisted because your child also has sensory integration issues.

< My Thoughts > “…sensory integration…”

Sensory integration (SI) is a term describing processes in the brain that allow us to receive and absorb the information we obtain from our environment. Such as, having the receptive ability for ‘motor learning’, ‘adaptive responses’, and ‘purposeful activities’.

Note: More about Sensory Integration in Unit 4 Chapter 3.

Gardner (2008) gives us a glimpse of her son Dale, at the age of fourteen months. Dale suddenly found his feet. There was no ‘in-between’ stage; one day he was crawling, the next he was literally up and running.

His running was repetitive, almost ritualistic, and without purpose. If anyone tried to stop him, he would respond with a tantrum so extreme that nothing we said or did would get through to him.

< My Thoughts > “…he would respond with a tantrum…”

Children with autism, when over stimulated through brain synapses, sensory overload, or whatever is playing out in their head at the time can react in a manner which looks like a tantrum, meltdown, or a ‘sensory episode’ of some kind. This action may be caused from a sense of sadness and/or anger and frustration, or a sense of happiness and jubilation.

When someone once reported that Sonny had been repeatedly hitting his head with a clenched fist. We asked – “Is it ‘happy’ hitting or ‘angry’ hitting?” Because at times he would be smiling and happy when he engaged in that behavior. Other times, he would be frowning, or grimacing with frustration, while severely clubbing himself on the head. Either behavior could be a result of an earlier insult (perceived or otherwise), or a previous sensory issue.

For example, we call it ‘angry’ hitting if he can’t find the puzzle piece he is looking for; or, if a scene on his video is over before he is ready for it to be. In the case of ‘happy’ hitting, he becomes overjoyed at the very same actions in reverse. He finds what he wants, or in Toy Story II video, Barbie makes Ken wear a funny outfit, and so on. Either way, the self-inflicted injuries are similarly’ severe’, whether Sonny is happy’ hitting or ‘angry’ hitting.

Gardner informed the medical professionals that Dale had developed a strange, tiptoe gait when walking, but they remained unconcerned. Now that he was walking, however, new and more challenging problems surfaced. He seemed to have no comprehension whatsoever of even the simplest language we were speaking.

< My Thoughts > “…tiptoe gait…”

Also, even ‘neuro-typical’ children will stop performing a learned behavior when in pursuit of a new more ‘interesting to them’ skill. The pediatrician may not be concerned about Dale’s ‘tiptoeing’ because it is sometimes seen in young children as they begin experimenting with their new mobility. And, the thought of ‘autism’ as the cause hasn’t immerged yet.

According to Harrop (2013), most children with autism will exhibit Restrictive Repetitive Behavior (RRBs) at some point, but NOT all kids will act that way persistently. In typical development, RRB’s will lead to mastery of a skill or task. Two kinds of RRB’s are seen in those with autism – ‘lower order’ and ‘higher order’ restrictive repetitive behaviors.

‘Lower order’ behaviors are characterized by repetitive manipulation of objects, like spinning a wheel or lining up cars. While ‘higher order’ behaviors are more ritualistic in nature, where the child will only walk a certain way across the room, for example.

Note: More about Restrictive Repetitive Behavior (RRBs) and Sensory Integration (SI), in UNIT 4.

Gardner continues – Dale would charge across the room, bounce himself off the wall to gain momentum, and race back again, droning continuously; sometimes in a happy tone, sometime anxious.

Kedar (2012) asks you to imagine living in a body that paces or flaps hands or twirls ribbons when your mind wants it to be still. Or, freezes when your mind pleads with it to react. You lie in a bed, cold, wishing you could get your body to pull on a blanket.

My proprioception is messed up. I need my eyes to tell me where my hands and legs are. This is hard because it means I have to visually pay attention to my body. It interferes with physical sports especially if I can’t see my legs. My exercising therapy helps me to feel my body more, more connected to my brain.

Or, when I am bored, frustrated, angry, misunderstood and feeling more than a little hopeless, I turn to repetitive behaviors. My stimulating behavior, or ‘stims’, create a sensory drug-like experience that takes me away from the pain but makes the situation so much worse by pulling me farther from reality.

< My Thoughts > “…pull on a blanket.”

“Wishing you could get your body to pull on a blanket.” There is a severe disconnection between Ido’s explicit intentional thoughts and his automatic ones. He can’t make himself pull up the blanket even though he sees it and knows what he wants to do.

He needs to be able to ‘self-generate’ the command to pull up the blanket, but he is helpless to do so because his brain wiring won’t allow him to initiate that mind-body connection. ‘Proprioception’ prevents pulling up a blanket while producing the ‘stimming’ which pulls him farther from reality.

Mostofsky (2014) marvels that many children with autism have difficulty with ‘self-generated’ commands. The reason for this has to do with the wiring of the brain and developing an internal model of behavior. Children with autism are sometimes impaired in their ability to acquire models of action because of their bias towards proprioceptive-guided motor learning. In other words, their motor learning is mostly directed by what their body senses, as opposed to what that person sees s/he should be doing.

Depending on the age of the child, probably the fact that s/he may not be meeting their 'developmental milestones' could be due to poor motor skills. Both 'gross' (using large muscles involving walking and/or easily moving the body) and 'fine' (involving pincer and/or grasping skills) should be developing as expected. But if they are NOT developing typically, that may be because motor skill deficits are affecting the child’s necessary mobility, keeping them from becoming their best ‘independent’ selves.

Menear, et al. (2006) tell us that their informal observations have shown that many students with autism who have ‘low’ motor skills and few fitness abilities will have initial difficulty in traversing typical school or park playground equipment without assistance. Poor eye-hand coordination, trouble combining multiple motor skills into one task, and any structured balance related physical activities, as well as participating in group activities can be difficult.

< My Thoughts > “…motor skills and few fitness abilities…”

What to do while you wait for doctors, diagnosis, and direction? Try teaching activities which develop ‘gross/large’ motor skills. This can be done with your child while you are ‘waiting’ for the ‘new’ world of doctor’s appointments, consultations, final diagnosis, and program possibilities to open up for you.

Autism related tiptoeing, clumsiness and tripping on stairs may be occasional and even subtle, but when it happens often enough then it can become a safety issue. And, added to other core symptoms may be about autism.

You might try two types of physical programs – aerobic and aquatic. Both can be ‘fun’ activities you can do with your child and/or find in your local area. Look for 'Challenger' or 'Adaptive' and ‘Alternative’ programs offered by community organizations. You don’t have to have the child’s ‘diagnoses’ to participate in most community adaptive/alternative activities. Plus, you may meet new friends there and possibly do important networking.

Note: More about ‘Networking’ in UNIT 6, Ch. 1.

Morin (2017) cautions that children’s preferences change over time. As your child ages, peers and other adults will encourage the pursuit of new interests. It's normal for a child to want to play different sports, hear new types of music and engage in new artistic activities.

< My Thoughts > “…pursuit of new interests.”

The ‘normally developing’ child eventually becomes interested in what others are doing. A child on the autistic spectrum seems mostly to be ‘self-involved’ with ‘preferred activities; lining-up toys, watching the same video repeatedly, and/or traveling the same paths over-and-over.

While getting to know your child, help to pursue new interests, understand his/her ‘fine / gross’ motor skills, and ‘fitness abilities’.

Parents may want to try ‘tying’ a new activity to a favorite one. For instance, Sonny loves to walk on our garden path; stopping to visit certain flowers, or ceramic frogs. We find ways to add new interests by stopping to sit on a bench to listen to a brief moment of music on a MP3 Player.

In another setting, a therapist suggested that we add a very short clip from a National Geographic show to the end of the ‘Blues Clues’ recording; which Sonny watches on a loop. At first, the added documentary clip about polar bears seemed to annoy him, but eventually he settled down and watched it. Mission accomplished!

Be cautious but unafraid. Work with your child to allow experimentation and growth. Over time, you will come up with additional safe, appropriate, and positive types of activities. Know also, that many ‘activities’ are resisted because your child also has sensory integration issues.

< My Thoughts > “…sensory integration…”

Sensory integration (SI) is a term describing processes in the brain that allow us to receive and absorb the information we obtain from our environment. Such as, having the receptive ability for ‘motor learning’, ‘adaptive responses’, and ‘purposeful activities’.

Note: More about Sensory Integration in Unit 4 Chapter 3.

Gardner (2008) gives us a glimpse of her son Dale, at the age of fourteen months. Dale suddenly found his feet. There was no ‘in-between’ stage; one day he was crawling, the next he was literally up and running.

His running was repetitive, almost ritualistic, and without purpose. If anyone tried to stop him, he would respond with a tantrum so extreme that nothing we said or did would get through to him.

< My Thoughts > “…he would respond with a tantrum…”

Children with autism, when over stimulated through brain synapses, sensory overload, or whatever is playing out in their head at the time can react in a manner which looks like a tantrum, meltdown, or a ‘sensory episode’ of some kind. This action may be caused from a sense of sadness and/or anger and frustration, or a sense of happiness and jubilation.

When someone once reported that Sonny had been repeatedly hitting his head with a clenched fist. We asked – “Is it ‘happy’ hitting or ‘angry’ hitting?” Because at times he would be smiling and happy when he engaged in that behavior. Other times, he would be frowning, or grimacing with frustration, while severely clubbing himself on the head. Either behavior could be a result of an earlier insult (perceived or otherwise), or a previous sensory issue.

For example, we call it ‘angry’ hitting if he can’t find the puzzle piece he is looking for; or, if a scene on his video is over before he is ready for it to be. In the case of ‘happy’ hitting, he becomes overjoyed at the very same actions in reverse. He finds what he wants, or in Toy Story II video, Barbie makes Ken wear a funny outfit, and so on. Either way, the self-inflicted injuries are similarly’ severe’, whether Sonny is happy’ hitting or ‘angry’ hitting.

Gardner informed the medical professionals that Dale had developed a strange, tiptoe gait when walking, but they remained unconcerned. Now that he was walking, however, new and more challenging problems surfaced. He seemed to have no comprehension whatsoever of even the simplest language we were speaking.

< My Thoughts > “…tiptoe gait…”

Also, even ‘neuro-typical’ children will stop performing a learned behavior when in pursuit of a new more ‘interesting to them’ skill. The pediatrician may not be concerned about Dale’s ‘tiptoeing’ because it is sometimes seen in young children as they begin experimenting with their new mobility. And, the thought of ‘autism’ as the cause hasn’t immerged yet.

According to Harrop (2013), most children with autism will exhibit Restrictive Repetitive Behavior (RRBs) at some point, but NOT all kids will act that way persistently. In typical development, RRB’s will lead to mastery of a skill or task. Two kinds of RRB’s are seen in those with autism – ‘lower order’ and ‘higher order’ restrictive repetitive behaviors.

‘Lower order’ behaviors are characterized by repetitive manipulation of objects, like spinning a wheel or lining up cars. While ‘higher order’ behaviors are more ritualistic in nature, where the child will only walk a certain way across the room, for example.

Note: More about Restrictive Repetitive Behavior (RRBs) and Sensory Integration (SI), in UNIT 4.

Gardner continues – Dale would charge across the room, bounce himself off the wall to gain momentum, and race back again, droning continuously; sometimes in a happy tone, sometime anxious.

Kedar (2012) asks you to imagine living in a body that paces or flaps hands or twirls ribbons when your mind wants it to be still. Or, freezes when your mind pleads with it to react. You lie in a bed, cold, wishing you could get your body to pull on a blanket.

My proprioception is messed up. I need my eyes to tell me where my hands and legs are. This is hard because it means I have to visually pay attention to my body. It interferes with physical sports especially if I can’t see my legs. My exercising therapy helps me to feel my body more, more connected to my brain.

Or, when I am bored, frustrated, angry, misunderstood and feeling more than a little hopeless, I turn to repetitive behaviors. My stimulating behavior, or ‘stims’, create a sensory drug-like experience that takes me away from the pain but makes the situation so much worse by pulling me farther from reality.

< My Thoughts > “…pull on a blanket.”

“Wishing you could get your body to pull on a blanket.” There is a severe disconnection between Ido’s explicit intentional thoughts and his automatic ones. He can’t make himself pull up the blanket even though he sees it and knows what he wants to do.

He needs to be able to ‘self-generate’ the command to pull up the blanket, but he is helpless to do so because his brain wiring won’t allow him to initiate that mind-body connection. ‘Proprioception’ prevents pulling up a blanket while producing the ‘stimming’ which pulls him farther from reality.

Mostofsky (2014) marvels that many children with autism have difficulty with ‘self-generated’ commands. The reason for this has to do with the wiring of the brain and developing an internal model of behavior. Children with autism are sometimes impaired in their ability to acquire models of action because of their bias towards proprioceptive-guided motor learning. In other words, their motor learning is mostly directed by what their body senses, as opposed to what that person sees s/he should be doing.

Davide-Rivera (2013) decides she had an obsession with walking on tiptoes. I always did. I’m told that I walked on my tiptoes everywhere I went, especially when I was very young.

“She has ballerina feet,” Grandma said, “look at her twirl, she’s a natural.” And so, off to ballet class I went. When I was dancing, and twirling, and listening to the music, I could drown the world out.

An intense focus allowed me to dance without mistake, because I could not tolerate mistakes. Everything had to be perfect; that is, ‘perfect’ the way I saw ‘perfect’. The only problem was I wanted to dance by myself. Soon I was given solos of my own to perform. I was a new little star.

It can be difficult to explain how we, those with Asperger’s Syndrome/Autism, can be so clumsy in our day-to-day activities, but so adept when we are intently focused. I spent a great deal of my life dancing. I could dance with the grace of a swan, yet fall down steps on my way off the stage.

< My Thoughts > “I could dance with grace… yet fall down steps…”

Clumsiness is a feature of ASD, but it is not necessarily needed to be present in an autism diagnosis. One reason may be that this specific motor-mind disorder is not clearly defined. Also there seems to be a variety of motor coordination problems possible with autism, some of which don’t become more obvious or severe until adolescence.

Davide-Rivera continues, asking – So why can I not keep my feet underneath me, or apply the correct amount of pressure when lifting an object? Why do I walk into a room like an elephant in a china shop? In a word – proprioception. What is proprioception?

Proprioception refers to one’s own perceptions. It’s an unconscious perception of movement and spatial orientation controlled by nerves within the body. Our proprioception system allows us to locate our bodies in space, to be aware of where our arms and legs are in relation to one another, as well as, where they begin and where they end.

Shiel (2020) – Proprioception is the ability to sense stimuli arising within the body regarding position, motion, and equilibrium. Even if a person is blindfolded, he or she knows through proprioception if an arm is above the head or hanging by the side of the body. The sense of proprioception is disturbed in many neurological disorders. It can sometimes be improved through the use of sensory integration therapy, a type of specialized occupational therapy.

Note: More about ‘Sensory Integration Therapy’ in UNIT 4, Ch. 3.

Sassano (2009) explains that – Proprioception is a sense of perception of the movements of one’s limbs, independent of vision. Typically developing children generalized in both ‘proprioceptive’ and ‘visual’ coordinates when generating models of behavior; whereas, children with autism only generalized in ‘proprioceptive’ coordinates. In other words, vision doesn’t play a role in their movement, only their body’s sensory field tells them where their body parts are and what they are doing.

Proprioception helps us perceive the outside world, telling us whether our bodies are moving or sitting still. This system helps us perceive the amount of force needed to complete a task, and then allows us to apply it appropriately. It helps us measure and perceive distances, allowing us to move through our world without crashing into everything around us.

Children and adults with autism often have difficulty with proprioception and it very well may be the thing that goes bump in the night, and in the day, and at work, and in the streets.

Poor proprioception may likely be responsible for those many bruises and skinned knees that plague our days.

A study by Ghaziuddin & Butler (1998) included 8 subtests for different parts of the anatomy. They were gross motor tests for running speed and agility, balance, bilateral coordination, upper limb coordination, and strength. Including fine motor tests for response speed, visual-motor control, and upper limb speed and dexterity. So, this doesn’t exactly answer the question of clumsiness, but does give one an idea of all the variables involved.

< My Thoughts > “…an idea of all the variables involved.”

Greater ability in one area and deficits in other motor-mind, mind-body areas might explain also our ‘clumsy’ ballerina (Davide-Rivera).

According to Zhao & Chen (2018) providing children with ASD the opportunity to participate in physical activities improves their physical condition, their self-esteem, social skills and their behavior. Often the child does not know how to interact with others in order to have that physical experience, but can be taught. And eventually children will exercise ‘spontaneously’, recognizing the need for that activity. Participants in the study had shown an improvement in parent/child interaction and the child’s interest in ‘otherworldly’ activities.

< My Thoughts > “…recognizing the need…”

Figuring out what your child can or cannot do, physically shouldn’t be a stressful activity, but one of enjoyment. And, if first you don’t succeed, try, try again. When the activity is just too difficult or stressful, the child should begin to show interest. Sonny often uses his peripheral vision to check out what you are doing. If we start bouncing a ball in the living room, he’ll stroll by several times, not acting interested, but taking a peek. Then, he goes in his room for a while, listening to the sound of me bouncing ball. Soon, he comes out and wants to hold the ball. That could be ‘it’ for the day, but we leave the ball out where he can find it.

The next day, he may go over, pick up the ball, and bring it to me. He much prefers to have us do the activity while he watches. He often giggles when you miss catching the bounce and the ball rolls across the room. After seeing the ball roll, we invite him to sit on the floor near us, letting the ball roll back and forth between us. Eventually, he begins participating in the ball rolling activity without realizing he has been tricked into playing ball with us. When he catches on, he gives us a ‘look’, gets up and goes in his room, sometimes smiling and sometimes annoyed. And so, it goes.

Jean (2006) just figures that appropriate, safe and comfortable exercise is important for lifelong fitness. The right exercise can also improve brain function, coordination and even memory. Most critical is ‘crossing-center-line’ training; which means you’re using both sides of the brain. ‘Cross-lateral’ movements are those in which arms and legs cross over from one side of the body to the other. An example would be to bend over at waist and tap right hand to an extended left foot. Back up and then bend and tap left hand to an extended right foot. This tends to ‘unstick’ the brain and energizes learning.

< My Thoughts > “…energizes learning.”

Sometimes in the classroom, having the students ‘unstick’ their brain for learning with this exercise really does work. Or, when the students become stressed or frustrated, we might go outside to run up and down the hallway to get our ‘sillies’ out, in this mind-body activity.

Rudy (2010) gives us a plan, “Get out, explore the community & have fun!” She tells us that individuals with autism are often too busy with therapies and doctors to think about physical fitness. Also, that performing in Adaptive Physical Education school programs start to fade away as students become teens and young adults.

< My Thoughts > “Get out, explore, have fun…”

Sonny likes to walk outdoors on a little pathway that we have created in our yard. He finds the interesting things which we have placed along the way. The things that we see we name, and stop to chat about. There are flowers to smell, plants to touch, birdhouses with occupants to watch. And of course, we just enjoy feeling the wind, seeing it blowing the colored ribbons we have tied in the trees. Objects can be labeled for those with higher learning abilities.

Sonny also enjoys attending an outdoor aquatic program, sponsored by the City Parks & Recreation. He has ‘somewhat’ participated in a “T” ball group that we found at a nearby park. Both programs allow us to participate with him, so it goes surprisingly well. We even ‘practice’ ‘T’ ball at home in the backyard, a ‘natural setting’ for him where he feels most comfortable. Look for 'Challenger' or 'Adaptive' programs near you. This is a great way to involve siblings, too.

“She has ballerina feet,” Grandma said, “look at her twirl, she’s a natural.” And so, off to ballet class I went. When I was dancing, and twirling, and listening to the music, I could drown the world out.

An intense focus allowed me to dance without mistake, because I could not tolerate mistakes. Everything had to be perfect; that is, ‘perfect’ the way I saw ‘perfect’. The only problem was I wanted to dance by myself. Soon I was given solos of my own to perform. I was a new little star.

It can be difficult to explain how we, those with Asperger’s Syndrome/Autism, can be so clumsy in our day-to-day activities, but so adept when we are intently focused. I spent a great deal of my life dancing. I could dance with the grace of a swan, yet fall down steps on my way off the stage.

< My Thoughts > “I could dance with grace… yet fall down steps…”

Clumsiness is a feature of ASD, but it is not necessarily needed to be present in an autism diagnosis. One reason may be that this specific motor-mind disorder is not clearly defined. Also there seems to be a variety of motor coordination problems possible with autism, some of which don’t become more obvious or severe until adolescence.

Davide-Rivera continues, asking – So why can I not keep my feet underneath me, or apply the correct amount of pressure when lifting an object? Why do I walk into a room like an elephant in a china shop? In a word – proprioception. What is proprioception?

Proprioception refers to one’s own perceptions. It’s an unconscious perception of movement and spatial orientation controlled by nerves within the body. Our proprioception system allows us to locate our bodies in space, to be aware of where our arms and legs are in relation to one another, as well as, where they begin and where they end.

Shiel (2020) – Proprioception is the ability to sense stimuli arising within the body regarding position, motion, and equilibrium. Even if a person is blindfolded, he or she knows through proprioception if an arm is above the head or hanging by the side of the body. The sense of proprioception is disturbed in many neurological disorders. It can sometimes be improved through the use of sensory integration therapy, a type of specialized occupational therapy.

Note: More about ‘Sensory Integration Therapy’ in UNIT 4, Ch. 3.

Sassano (2009) explains that – Proprioception is a sense of perception of the movements of one’s limbs, independent of vision. Typically developing children generalized in both ‘proprioceptive’ and ‘visual’ coordinates when generating models of behavior; whereas, children with autism only generalized in ‘proprioceptive’ coordinates. In other words, vision doesn’t play a role in their movement, only their body’s sensory field tells them where their body parts are and what they are doing.

Proprioception helps us perceive the outside world, telling us whether our bodies are moving or sitting still. This system helps us perceive the amount of force needed to complete a task, and then allows us to apply it appropriately. It helps us measure and perceive distances, allowing us to move through our world without crashing into everything around us.

Children and adults with autism often have difficulty with proprioception and it very well may be the thing that goes bump in the night, and in the day, and at work, and in the streets.

Poor proprioception may likely be responsible for those many bruises and skinned knees that plague our days.

A study by Ghaziuddin & Butler (1998) included 8 subtests for different parts of the anatomy. They were gross motor tests for running speed and agility, balance, bilateral coordination, upper limb coordination, and strength. Including fine motor tests for response speed, visual-motor control, and upper limb speed and dexterity. So, this doesn’t exactly answer the question of clumsiness, but does give one an idea of all the variables involved.

< My Thoughts > “…an idea of all the variables involved.”

Greater ability in one area and deficits in other motor-mind, mind-body areas might explain also our ‘clumsy’ ballerina (Davide-Rivera).

According to Zhao & Chen (2018) providing children with ASD the opportunity to participate in physical activities improves their physical condition, their self-esteem, social skills and their behavior. Often the child does not know how to interact with others in order to have that physical experience, but can be taught. And eventually children will exercise ‘spontaneously’, recognizing the need for that activity. Participants in the study had shown an improvement in parent/child interaction and the child’s interest in ‘otherworldly’ activities.

< My Thoughts > “…recognizing the need…”

Figuring out what your child can or cannot do, physically shouldn’t be a stressful activity, but one of enjoyment. And, if first you don’t succeed, try, try again. When the activity is just too difficult or stressful, the child should begin to show interest. Sonny often uses his peripheral vision to check out what you are doing. If we start bouncing a ball in the living room, he’ll stroll by several times, not acting interested, but taking a peek. Then, he goes in his room for a while, listening to the sound of me bouncing ball. Soon, he comes out and wants to hold the ball. That could be ‘it’ for the day, but we leave the ball out where he can find it.

The next day, he may go over, pick up the ball, and bring it to me. He much prefers to have us do the activity while he watches. He often giggles when you miss catching the bounce and the ball rolls across the room. After seeing the ball roll, we invite him to sit on the floor near us, letting the ball roll back and forth between us. Eventually, he begins participating in the ball rolling activity without realizing he has been tricked into playing ball with us. When he catches on, he gives us a ‘look’, gets up and goes in his room, sometimes smiling and sometimes annoyed. And so, it goes.

Jean (2006) just figures that appropriate, safe and comfortable exercise is important for lifelong fitness. The right exercise can also improve brain function, coordination and even memory. Most critical is ‘crossing-center-line’ training; which means you’re using both sides of the brain. ‘Cross-lateral’ movements are those in which arms and legs cross over from one side of the body to the other. An example would be to bend over at waist and tap right hand to an extended left foot. Back up and then bend and tap left hand to an extended right foot. This tends to ‘unstick’ the brain and energizes learning.

< My Thoughts > “…energizes learning.”

Sometimes in the classroom, having the students ‘unstick’ their brain for learning with this exercise really does work. Or, when the students become stressed or frustrated, we might go outside to run up and down the hallway to get our ‘sillies’ out, in this mind-body activity.

Rudy (2010) gives us a plan, “Get out, explore the community & have fun!” She tells us that individuals with autism are often too busy with therapies and doctors to think about physical fitness. Also, that performing in Adaptive Physical Education school programs start to fade away as students become teens and young adults.

< My Thoughts > “Get out, explore, have fun…”

Sonny likes to walk outdoors on a little pathway that we have created in our yard. He finds the interesting things which we have placed along the way. The things that we see we name, and stop to chat about. There are flowers to smell, plants to touch, birdhouses with occupants to watch. And of course, we just enjoy feeling the wind, seeing it blowing the colored ribbons we have tied in the trees. Objects can be labeled for those with higher learning abilities.

Sonny also enjoys attending an outdoor aquatic program, sponsored by the City Parks & Recreation. He has ‘somewhat’ participated in a “T” ball group that we found at a nearby park. Both programs allow us to participate with him, so it goes surprisingly well. We even ‘practice’ ‘T’ ball at home in the backyard, a ‘natural setting’ for him where he feels most comfortable. Look for 'Challenger' or 'Adaptive' programs near you. This is a great way to involve siblings, too.

PART 1 – Poor Eating

Another continual parent concern is in the area of ‘poor eating’ skills. Causes for this could be many; including fine/gross motor skills. Understanding what parents can do might be helpful.

Menear, et al. (2006) mark poor eye-hand coordination and trouble combining multiple motor skills into one task as a possible cause. As well as the difficulty performing any structured balance related physical activities.

< My Thoughts > “…Poor eye-hand coordination…”

Although studies are few, it seems to me that poor eye-hand coordination could possibly be the cause of poor eating abilities. Most typical babies at an early age figure out how to shove everything into their mouths. Think about the eye-hand coordination and multitasking it takes to accomplish that skill for the first time, let alone to accomplish it repeatedly.

Davide-Rivera (2013) discloses – When smells overwhelmed me, I had a sensitive stomach. When I only ate a few select items, I was a picky eater.

< My Thoughts > “…picky eater...”

Picky eating may not be a problem unless the child’s growth is affected, or unless allergies are suspected. Many children go through periods of not wanting foods with certain tastes, textures, or temperatures. With some children this could well be a ‘sensory’ issue. Sonny has times when he eats only the red or green things he sees on his plate. This has something to do with those colors being visually pleasing and nothing to do with the fact that it is Christmas. Maybe!

But for those persistently picky eaters, Schneider (2012) tells everyone who will listen what he thinks about food, in his children’s book. He loves recounting his childhood refusal to eat disgusting, smelly, repulsive, lumpy, or slimy foods. That is, until his father introduces some bold and daring meal choices.

Bogdashina & Casanova (2016) tell us that the sense of smell, ‘olfaction’, has in its olfactory system 10 million smell receptors of 20 different types, in the nose. These nostril receptors respond quickly, guiding the chemicals in the air to be received by the senses. But the intensity of the smell is lost very rapidly.

Some autistic individuals however, have hyper-olfactory sensitivities, comparable to that of canines. To them, the smell or taste of food can be intolerable, no matter how hungry they are. For that reason, they will only eat certain foods.

Some children with ‘hypo-sensitivity’ will chew and smell everything around them. They will lick objects, play with feces, and easily regurgitate at will. Our sense of taste is not very strong because one’s tastes operates primarily on the chemicals in the liquids we are tasting. Compared to the sense of smell which operates on chemicals we smell in the air.

The authors go on to say that for some, the association of a particular smell with a feeling of calm, as during a soothing body massage, can trigger positive emotions. But the opposite may also be true, if for some reason a ‘smell’ may trigger a negative emotion. When this happens, the individual may experience nausea, or even outbursts of emotion, as well as the need of covering or rubbing their nose.

Howe & Stagg (2016) discuss the experiences some have with ‘smell’ sensitivity. They say that many can have a ‘positive’ reaction to an environmental smell, while others can feel anything from severe physical discomfort to mere annoyance. Some say that certain smells make them feel stressful, anxious, and/or provoked. And these sensitive reactions varied greatly in their intensity from mild to extreme.

Jones (2013) – If the child with autism doesn’t have ‘sameness’ they may express their discomfort by having a meltdown. There are ways to desensitize one to this situation, but it is an intervention process and doesn’t come automatically by introducing change in the setting.

< My Thoughts > “…‘sameness’…”

‘Sameness’ may be very essential to a child with autism because dealing with change or differences in intolerable. Taking Sonny a different way on a drive, or when one expected thing does NOT follow another expected thing can totally ruin his day. Sometimes, as with Sonny, it has something to do with exhibiting an Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

Jones jests that most people don’t like leftovers. As an Asperger adult, I am thrilled when I have leftovers, provided they weren’t horrible the first time around. It means that I don’t have to think about food and I can eat something predictable. The sameness of food.

One of the things that helped me tolerate the huge stress of school was the fact that my mother packed the same lunch for me daily. Every day, I would have a sandwich made from peanut butter and sliced sweet pickles on whole wheat bread, with carrot sticks, and lemonade. There was one thing I could count on every day and that was the ‘sameness’ of lunch.

< My Thoughts > “…the sameness of lunch…”

The sameness of food. As I understand it, in a more general sense might be mistaken for just being going through a ‘picky eater’ stage which many typical children go through. Insisting on the ‘sameness of food’ in children, adolescents, and adults with ASD seems to be a more of a manifestation of something in their environment that they are NOT easily processing. It could be that eating brings on certain degree of anxiety or there may even be a real apprehension of the eating process. Again, there are successful interventions to help with ‘picky eating’ for those on the autism spectrum.

One parent reported that her high-functioning child became very intense when it came to food. Needed to know where it came from before he got it, after he ate it, and where it went after he swallowed. She actually created picture and word storyboard, as well as video scenarios for him on how food is grown, harvested, marketed, etc. (Good way to teach ‘sequencing’ at the same time). Then, she showed him diagrams of the digestive process.

How from there it ‘goes in here and comes out there’. Gradually, he was able to trust that eating was okay and was something that he must do to stay healthy. At this point, the origin of the eating problem may not matter as much as figuring out a way to have the child accept the food, because, “Here comes the airplane (food on a spoon headed towards his mouth) open the hanger!”, is most likely not going to work.

Sicile-Kira (2014) explains that parents may be concerned when a child will eat only certain foods. It seems they don’t like change and may also insist on the same cup, plate, spoon, etc. They may always smell the food before eating it, or even start chewing on non-food items from time to time, instead of food.

This can be related to many things – their inflexible adherence to routines, sensory issues with certain texture or noisy foods. Perhaps they can only tolerate certain foods for sensory reasons. Some parents will have their children tested for food allergies, in case that might be the cause.

As humans, Sicile-Kira says that we need certain fundamental nutrients for our bodies to function well and these include certain vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids, amino acids from protein and certain fats. Blood and urine lab tests measure how a child metabolized food, which in turn impacts your child’s growth and development. The most common complaint is something like this – “My son ate macaroni and cheese for a whole month straight; morning, noon, and night. Now he’ll only eat peanut butter and jelly on hotdog buns!”

Jones, (2013) explains, I have a hard time with the executive function cognitive skills required to cook elaborate food, so I have learned to cook in a slow cooker or use a high-speed blender. I try to learn a new recipe at least once a month. I make sure I have a variety of food. The easier I can make it to get food onto my plate, the more likely I will eat well. Still, I sometimes forget to eat. I sometimes wander off in the middle of a meal and forget to finish it.

Siri & Lyons (2014) state that ‘hypo-sensitivity’, ‘hyper-sensitivity’ or ‘mixed-sensitivity’ occurs when the brain does not efficiently process information coming from the body, or the environment. Children with (low) ‘hypo-sensitivity’ require increased intensity in taste, texture, and/or temperature in order to process sensations. These children tend to prefer crunchy textures, and strong flavors.

Christol, et al. (2018) comment about children’s overly selective food patterns and lack of food variety puts them at risk for nutritional inadequacies. They found that more children with ASD present with an oral sensory sensitivity resulting in refusal of new foods, especially fruits and vegetables. Mentioned also is that each child’s sensory characteristics elucidates the nature of their relationship with ‘food sensitivity’ and ‘selectivity’. The understanding of this, and of food texture and consistency issues observed by parents, is often included in a child’s Sensory Profile.

Note: More about a Sensory Profile in the book’s Sensory Unit.

Mosheim (2011) makes us aware of a ‘food chaining’ therapy approach to help children expand their diets by using their favorite foods or drinks as a launching pad to gradually expand their eating repertoire. They may appear ‘picky’, but in many cases they are probably avoiding particular foods because they don't know how to eat them successfully. Some children with autism haven’t developed the ability or the skills to do well at eating, possibly due to developmental delays.

< My Thoughts > “…‘food chaining’ therapy approach…”

My experience with ‘food chaining’ is limited, but I’ve seen dedicated Occupational and Speech therapists, as well as specialized dieticians who strive so hard to problem solve feeding and eating issues for our kiddos. When Sonny began living with us as a 7-year-old foster child, we noticed that he had trouble chewing. First, because his permanent teeth came in late and second, because he only had learned one eating skill – sucking.

The therapist suspected that because his primary source of food was provided through sucking on a ‘sippy’ cup, he didn’t recognize when solid food was in his mouth. Nor, what to do with food once it was there. Thus, introducing the texture of something he couldn’t ignore, a bagel with peanut butter. Eventually (about a year) he was able to chew and swallow his peanut butter topped bagel bites. Major accomplishment!

When solving a child’s eating problems, first, the therapist rules out any physical problems in chewing, swallowing, digesting, or other stressors. Once that’s determined, they begin to find out what types of food the child does like to eat. Do they like gummy and chewy, or crispy and crunchy? Sometimes by disguising new foods, they are able to build the child’s food repertoire to include the more necessary nutritional components.

Note: Food Chaining was developed by Fraker, C., Walbert, L., of the Mill Medical Center and Cox, S., of the University of So. IL School of Medicine and is used for children with feeding/eating disorders.

< My Thoughts > “…the more necessary…”

Sonny’s daily intake of powerful drugs requires nutritional support to be effective. The medicine bottle clearly says – “Take with food.” The reason is not just so it won’t cause an upset stomach, but so it will be carried into the bloodstream, or wherever it needs to go to do the job. Some of his ‘horse pills’ cannot easily be broken-up, sprinkled, or otherwise disguised in food. This can become an issue. A stated side-effect of one med is ‘difficulty swallowing’. Wow! They don’t make it easy, do they? And some days his lips and/or mouth are so dry (another med side-effect) and just have to be lubricated before he can try to take anything in.

Another continual parent concern is in the area of ‘poor eating’ skills. Causes for this could be many; including fine/gross motor skills. Understanding what parents can do might be helpful.

Menear, et al. (2006) mark poor eye-hand coordination and trouble combining multiple motor skills into one task as a possible cause. As well as the difficulty performing any structured balance related physical activities.

< My Thoughts > “…Poor eye-hand coordination…”

Although studies are few, it seems to me that poor eye-hand coordination could possibly be the cause of poor eating abilities. Most typical babies at an early age figure out how to shove everything into their mouths. Think about the eye-hand coordination and multitasking it takes to accomplish that skill for the first time, let alone to accomplish it repeatedly.

Davide-Rivera (2013) discloses – When smells overwhelmed me, I had a sensitive stomach. When I only ate a few select items, I was a picky eater.

< My Thoughts > “…picky eater...”

Picky eating may not be a problem unless the child’s growth is affected, or unless allergies are suspected. Many children go through periods of not wanting foods with certain tastes, textures, or temperatures. With some children this could well be a ‘sensory’ issue. Sonny has times when he eats only the red or green things he sees on his plate. This has something to do with those colors being visually pleasing and nothing to do with the fact that it is Christmas. Maybe!

But for those persistently picky eaters, Schneider (2012) tells everyone who will listen what he thinks about food, in his children’s book. He loves recounting his childhood refusal to eat disgusting, smelly, repulsive, lumpy, or slimy foods. That is, until his father introduces some bold and daring meal choices.

Bogdashina & Casanova (2016) tell us that the sense of smell, ‘olfaction’, has in its olfactory system 10 million smell receptors of 20 different types, in the nose. These nostril receptors respond quickly, guiding the chemicals in the air to be received by the senses. But the intensity of the smell is lost very rapidly.

Some autistic individuals however, have hyper-olfactory sensitivities, comparable to that of canines. To them, the smell or taste of food can be intolerable, no matter how hungry they are. For that reason, they will only eat certain foods.

Some children with ‘hypo-sensitivity’ will chew and smell everything around them. They will lick objects, play with feces, and easily regurgitate at will. Our sense of taste is not very strong because one’s tastes operates primarily on the chemicals in the liquids we are tasting. Compared to the sense of smell which operates on chemicals we smell in the air.

The authors go on to say that for some, the association of a particular smell with a feeling of calm, as during a soothing body massage, can trigger positive emotions. But the opposite may also be true, if for some reason a ‘smell’ may trigger a negative emotion. When this happens, the individual may experience nausea, or even outbursts of emotion, as well as the need of covering or rubbing their nose.

Howe & Stagg (2016) discuss the experiences some have with ‘smell’ sensitivity. They say that many can have a ‘positive’ reaction to an environmental smell, while others can feel anything from severe physical discomfort to mere annoyance. Some say that certain smells make them feel stressful, anxious, and/or provoked. And these sensitive reactions varied greatly in their intensity from mild to extreme.

Jones (2013) – If the child with autism doesn’t have ‘sameness’ they may express their discomfort by having a meltdown. There are ways to desensitize one to this situation, but it is an intervention process and doesn’t come automatically by introducing change in the setting.

< My Thoughts > “…‘sameness’…”

‘Sameness’ may be very essential to a child with autism because dealing with change or differences in intolerable. Taking Sonny a different way on a drive, or when one expected thing does NOT follow another expected thing can totally ruin his day. Sometimes, as with Sonny, it has something to do with exhibiting an Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

Jones jests that most people don’t like leftovers. As an Asperger adult, I am thrilled when I have leftovers, provided they weren’t horrible the first time around. It means that I don’t have to think about food and I can eat something predictable. The sameness of food.

One of the things that helped me tolerate the huge stress of school was the fact that my mother packed the same lunch for me daily. Every day, I would have a sandwich made from peanut butter and sliced sweet pickles on whole wheat bread, with carrot sticks, and lemonade. There was one thing I could count on every day and that was the ‘sameness’ of lunch.

< My Thoughts > “…the sameness of lunch…”

The sameness of food. As I understand it, in a more general sense might be mistaken for just being going through a ‘picky eater’ stage which many typical children go through. Insisting on the ‘sameness of food’ in children, adolescents, and adults with ASD seems to be a more of a manifestation of something in their environment that they are NOT easily processing. It could be that eating brings on certain degree of anxiety or there may even be a real apprehension of the eating process. Again, there are successful interventions to help with ‘picky eating’ for those on the autism spectrum.

One parent reported that her high-functioning child became very intense when it came to food. Needed to know where it came from before he got it, after he ate it, and where it went after he swallowed. She actually created picture and word storyboard, as well as video scenarios for him on how food is grown, harvested, marketed, etc. (Good way to teach ‘sequencing’ at the same time). Then, she showed him diagrams of the digestive process.

How from there it ‘goes in here and comes out there’. Gradually, he was able to trust that eating was okay and was something that he must do to stay healthy. At this point, the origin of the eating problem may not matter as much as figuring out a way to have the child accept the food, because, “Here comes the airplane (food on a spoon headed towards his mouth) open the hanger!”, is most likely not going to work.

Sicile-Kira (2014) explains that parents may be concerned when a child will eat only certain foods. It seems they don’t like change and may also insist on the same cup, plate, spoon, etc. They may always smell the food before eating it, or even start chewing on non-food items from time to time, instead of food.

This can be related to many things – their inflexible adherence to routines, sensory issues with certain texture or noisy foods. Perhaps they can only tolerate certain foods for sensory reasons. Some parents will have their children tested for food allergies, in case that might be the cause.

As humans, Sicile-Kira says that we need certain fundamental nutrients for our bodies to function well and these include certain vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids, amino acids from protein and certain fats. Blood and urine lab tests measure how a child metabolized food, which in turn impacts your child’s growth and development. The most common complaint is something like this – “My son ate macaroni and cheese for a whole month straight; morning, noon, and night. Now he’ll only eat peanut butter and jelly on hotdog buns!”

Jones, (2013) explains, I have a hard time with the executive function cognitive skills required to cook elaborate food, so I have learned to cook in a slow cooker or use a high-speed blender. I try to learn a new recipe at least once a month. I make sure I have a variety of food. The easier I can make it to get food onto my plate, the more likely I will eat well. Still, I sometimes forget to eat. I sometimes wander off in the middle of a meal and forget to finish it.

Siri & Lyons (2014) state that ‘hypo-sensitivity’, ‘hyper-sensitivity’ or ‘mixed-sensitivity’ occurs when the brain does not efficiently process information coming from the body, or the environment. Children with (low) ‘hypo-sensitivity’ require increased intensity in taste, texture, and/or temperature in order to process sensations. These children tend to prefer crunchy textures, and strong flavors.

Christol, et al. (2018) comment about children’s overly selective food patterns and lack of food variety puts them at risk for nutritional inadequacies. They found that more children with ASD present with an oral sensory sensitivity resulting in refusal of new foods, especially fruits and vegetables. Mentioned also is that each child’s sensory characteristics elucidates the nature of their relationship with ‘food sensitivity’ and ‘selectivity’. The understanding of this, and of food texture and consistency issues observed by parents, is often included in a child’s Sensory Profile.

Note: More about a Sensory Profile in the book’s Sensory Unit.

Mosheim (2011) makes us aware of a ‘food chaining’ therapy approach to help children expand their diets by using their favorite foods or drinks as a launching pad to gradually expand their eating repertoire. They may appear ‘picky’, but in many cases they are probably avoiding particular foods because they don't know how to eat them successfully. Some children with autism haven’t developed the ability or the skills to do well at eating, possibly due to developmental delays.

< My Thoughts > “…‘food chaining’ therapy approach…”

My experience with ‘food chaining’ is limited, but I’ve seen dedicated Occupational and Speech therapists, as well as specialized dieticians who strive so hard to problem solve feeding and eating issues for our kiddos. When Sonny began living with us as a 7-year-old foster child, we noticed that he had trouble chewing. First, because his permanent teeth came in late and second, because he only had learned one eating skill – sucking.

The therapist suspected that because his primary source of food was provided through sucking on a ‘sippy’ cup, he didn’t recognize when solid food was in his mouth. Nor, what to do with food once it was there. Thus, introducing the texture of something he couldn’t ignore, a bagel with peanut butter. Eventually (about a year) he was able to chew and swallow his peanut butter topped bagel bites. Major accomplishment!

When solving a child’s eating problems, first, the therapist rules out any physical problems in chewing, swallowing, digesting, or other stressors. Once that’s determined, they begin to find out what types of food the child does like to eat. Do they like gummy and chewy, or crispy and crunchy? Sometimes by disguising new foods, they are able to build the child’s food repertoire to include the more necessary nutritional components.

Note: Food Chaining was developed by Fraker, C., Walbert, L., of the Mill Medical Center and Cox, S., of the University of So. IL School of Medicine and is used for children with feeding/eating disorders.

< My Thoughts > “…the more necessary…”

Sonny’s daily intake of powerful drugs requires nutritional support to be effective. The medicine bottle clearly says – “Take with food.” The reason is not just so it won’t cause an upset stomach, but so it will be carried into the bloodstream, or wherever it needs to go to do the job. Some of his ‘horse pills’ cannot easily be broken-up, sprinkled, or otherwise disguised in food. This can become an issue. A stated side-effect of one med is ‘difficulty swallowing’. Wow! They don’t make it easy, do they? And some days his lips and/or mouth are so dry (another med side-effect) and just have to be lubricated before he can try to take anything in.

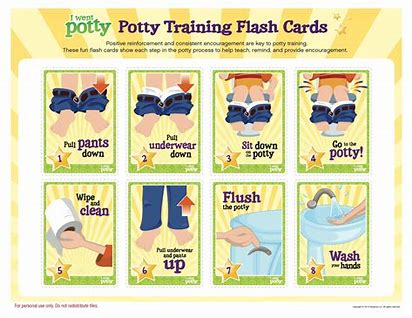

PART 2 – Toilet Training

Gulsrud, et al. (2018) give us suggestions from this study that there may be deficits in gross and fine motor skills which are preventing successful toileting. Motor skills can be most concerning when delayed, or even limited. In this study, ‘parent-rated’ autistic behaviors, noted the distinction as to how the child’s toileting difficulties varied and to what extent the child’s difficulties were ‘problematic’ for the child. Parent-ratings were shown as happening – Never, Sometimes, or Often. Clarifying that when the problem was rated as ‘often’ then the decision for early intervention was more easily decided by clinicians and parents.

Isaacson (2009) says about his 5-year-old son, “When we went out to Mongolia, Rowan was incontinent, had tantrums all the time, and was unable to make friends. And when we came back, he was without those three dysfunctions. Rowan continues to do better.”

Life with Rowan meant tantrums like tsunamis, like storm fronts moving in from nowhere, erupting even in his sleep. No language. My son was floating away from me, absent, not there. So tantalizingly affectionate one moment and so lost the next.

“Code Brown!” I shouted, which sent Kristin darting into the van to grab the small blue plastic bucket, brush and two-liter bottle of water. “Gotta get all clean,” Rowan whined. “More shamans!” Rowan shouted, as I took my son in my arms and put him in the van. “More shamans!”

< My Thoughts > “Code Brown!”

Before completing their visit with the shamans in Mongolia, Rowan had trouble controlling his bowels. A common family alarm which sounded was, “Code Brown!”

The light rain in Mongolia began to intensify once more, “The gods are happy,” Tulga was translating. “The rain shows that the Lords of the Mountains have accepted for Rowan to be healed. It is a very good sign.”

The shaman Ghoste told me, “Rowan will become gradually less autistic until his ninth year. Then, if you follow instructions, his autism will get less and less, and gradually disappear. But the dysfunctions, like the incontinence, the tantrums, these things will end now. From today.”

I tried to take this in, found I couldn’t. So, I just kept listening.

Since we left Namibia, Rowan was back to using the toilet once more. The tantrums, after the last mega-eruption had gone into abeyance.

< My Thoughts > “Since we left Namibia…”

Not many of us have the courage, connections, or the wherewithal to take our child to Mongolia to visit shamans. Even if we would like to.

Leader, et al. (2018) learned about many parents who are concerned that barriers to successful toilet training could be from medical issues, Gastrointestinal (GI) issues or an impacted colon. They discuss the necessary steps of toileting as – communicating toileting needs, undress, sit on toilet, relax and release bowels and/or bladder, know when finished, use toilet paper, stand, redress, and flush the toilet. Also discussed as ‘problems’ were bowel and bladder leakage, as well as voiding urine and/or defecating in inappropriate places. Other parental concerns were that this inability to be successfully toilet trained would cause their child to continually be restricted or removed from desired places or activities.

Note: When it comes to aquatic programs, incontinent youth in diapers are usually prohibited. Very few children with severe autism are toilet trained until they are way beyond the toddler stage. Thus, limiting entrance to many community group activities.

Bennie (2019) blogs that it took 3 years to train her son for a bowel movement. He was frequently constipated and liked to smear his feces around. Saying it was easier to give in to using Pull-Ups than handling the messy cleanup. Finally, with persistence, at age 9.5 years, he became toilet trained.

She gives what she believes are the two main contributing factors to the toileting difficulties experienced by persons with autism –

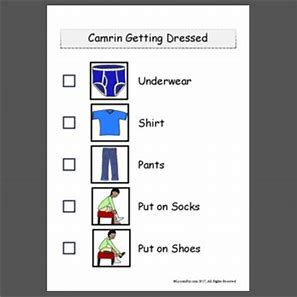

Another added difficulty she suggests is that the unfamiliarity of different types of toilets could be confusing. More confusion could come from wearing Pull-Ups when going out during the day, or going to bed at night after being expected to use the toilet at other times. More difficulty may come from the inability to relax, while on the toilet. This, it’s suggested, could be helped by letting the child blow bubbles with a simple bubble blowing toy, while seated on the toilet. Also effective is sticking to a continual toileting routine, and/or making certain the child feels comfortable when toileting.

< My Thoughts > “…child feels comfortable…”

Knowing your child and what makes them comfortable is very important to successful training of any kind. Some children need a small ramp or step, in order to get up on the toilet independently. There are all kinds seats available, too; some with smaller openings, and some with armrests. Many parents and teachers when training, have boys raise the toilet seats as part of the routine of standing and voiding into the toilet bowl. Sometimes aiming at a couple of ‘Cheerio’s’ placed there as targets may help that process.

When we trained Sonny, ‘sitting’ on the toilet seat for both functions seemed much less confusing and easier. Voiding in the toilet while seated left his hands free to hold a book, or use a bubble making toy.

His main difficulties became undressing and redressing, more so than with the other functions. One step he has never mastered alone is handwashing after toileting. This still requires hand-over-hand prompting. But he does respond to scheduled toileting, 20 – 30 minutes after meals. He has become quite good at using his CheapTalk augmentative communication board to say, “Bathroom, please.”

Because Sonny also ‘signs’ his needs, for toileting we had to learn and teach these necessary signs – toilet, stop, sit-down, stand-up, walk forward, back-up, release (when he’s grabbing something too tightly), and to sign ‘finished’ when he is. He sometimes signs ‘finished’ when he thinks he is, or when he doesn’t want to sit there any longer. We always give him control over that situation, because we’ve learned to prioritize his needs over our needs, and because it builds trust.

Decker (2011) I wish I were engulfed in flames. Hail Mary, full of grace, is there a flamethrower in the vicinity? It was a dark and stormy day. On this particular day, we went to Rite Aid to get a new prescription for Jaxson, the third in a series of medications to try and help prevent his aggressive behavior, particularly after starting school.

In the store, he went into a full-on hysteria-inducing temper tantrum because I would not purchase another camera to replace the one he had flushed down the toilet the night before. The toilet was unscathed – the camera, however, hadn’t been so lucky.

< My Thoughts > “…one he had flushed down the toilet…”

This is probably one of the reasons that parents and teachers can never agree as to whether the child should be allowed to take a book, or toys with them into the bathroom. As a teacher, I would weigh my options.

Sometimes, the child didn’t even know s/he was being led into the bathroom, if they were on their iPad. But vigilance is required to make certain that valuable piece of technology doesn’t land in the toilet. So many stories about things that get flushed. Jeni Decker’s son was probably just trying to get an action shot of swirling blue water with his camera.

This also brings up the possibility that as with Sonny’s ‘behavior’ meds, Jaxson’s new prescription may have many side effects, which could involve either constipation or diarrhea. This of course will require an abrupt change in the toileting routine.