Unit 7 – 7 Complementary & Alternative Medicine (CAMs) PART 4

7. creative therapy – Introduction, a. art, b. dance,

c. music, d. theatre, e. adventure therapy

8. facilitated communication

NOTE: PROCEED WITH CAUTION. Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAMs) treatments are still very controversial and may even be very dangerous. Before starting any treatment program, investigate thoroughly, and ALWAYS, ALWAYS talk to your child’s doctor first.

(NOTE: ‘Intervention’ disclaimer is also provided in introduction to INTERVENTIONS, and in OTHER THERAPIES)

PLEASE READ DISCLAIMER

Unit 7 – 7 Complementary & Alternative Medicine (CAMs) Section 7

Who May Help? PART 4 –

7. Creative Therapy – Introduction;

a. Art, b. Dance, c. Music, & d. Theatre) &

e. Adventure Therapy

7. creative therapy – Introduction, a. art, b. dance,

c. music, d. theatre, e. adventure therapy

8. facilitated communication

NOTE: PROCEED WITH CAUTION. Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAMs) treatments are still very controversial and may even be very dangerous. Before starting any treatment program, investigate thoroughly, and ALWAYS, ALWAYS talk to your child’s doctor first.

(NOTE: ‘Intervention’ disclaimer is also provided in introduction to INTERVENTIONS, and in OTHER THERAPIES)

PLEASE READ DISCLAIMER

Unit 7 – 7 Complementary & Alternative Medicine (CAMs) Section 7

Who May Help? PART 4 –

7. Creative Therapy – Introduction;

a. Art, b. Dance, c. Music, & d. Theatre) &

e. Adventure Therapy

INTRODUCTION – CREATIVE THERAPY

Creative therapy here covers a. Art therapy, b. Dance therapy, c. Music therapy, d. Theatre therapy, e. Adventure therapy.

Tubbs (2007) talks about parents, who’ve seen moments of awareness in their children which have surprised and delighted them. When all three are synchronized, the spiritual, the body and mind we have an integrated human being, even with autism.

Your child’s spiritual nature may flash through in times of joy or interest. Children with autism can be moved by classical music or beautiful colors and encouraged to paint wonderful pictures.

With creative therapies parents can facilitate changes in their child by using many of the same techniques a therapist does, gaining momentum in weekly sessions.

< My Thoughts > “…parents can facilitate changes…”

Ask your child’s therapist for ways that you, as the parent, can extend or create ‘home’ sessions. If there is no therapist present, then try drawing the things that you liked to draw or paint at your child’s age. Or, if music or dance was your secret passion, create a little session for yourself wearing scarves, silly hats, etc. See if you can generate some interest from your child.

Rudy (2020) thinks that if your child might be interested in music, visual arts, acting or dancing then s/he may respond well to art therapies. These are out-of-pocket programs which may build skills and expand boundaries, but may be costly.

Squaresky (2014) says the slowness and expense of speech class frustrated me. So, we also tried movement therapy. Greg loved dancing and music. His music therapist, Elise wanted to help Greg find himself, develop his missing skills and understand that he controlled facial expressions.

In particular, Greg enjoyed watching himself in the mirror which covered a full wall of the church basement where he had therapy. He made faces as the therapist helped him discover emotions and how to express them.

She casually and skillfully entered his personal space to wake him up to life’s wonders. Interaction with other human beings was another objective.

Music therapy became a highlight of our lives. Greg played with instruments from all over the world as the music instructor, Jackie, interacted with him.

a. Art therapy

Scope, et al. (2017) reported that art therapy is considered to be an acceptable treatment for the majority of respondents. Saying that art therapy can involve using painting, clay work, and other creative visual art-making art forms; including creative digital media. There is no definitive criterion for those routinely referred for this therapy, according to these authors. The populations considered here were non-psychotic respondents with anxiety, depression and stress management issues; plus, art therapy is suggested to reduce the person’s isolation, due to autism.

Art therapy in this study is effective in a variety of settings and for a range of populations. In most situations the art therapy was delivered in a group setting where respondents felt that relationships with other members were established. Usually, participants and/or their parents felt that the time invested in art therapy was most helpful. When the therapist examined the result of their art-making with them, they were able to express their feelings about it. Most participants were reported to have better communication through artwork and even seemed to experience increased pride in expressing their thoughts and feelings through their art.

Lacour (2018) learned that Grant’s compulsive paper-tearing habit was turned into creating beautiful collages. Channeling ‘non-functioning’, stimming behavior into a creative outlet. People with autism often think in pictures. Art therapy seems to be a perfect fit for those with autism, she believes.

One of the most common goals in art therapy is to increase tolerance for unpleasant stimuli, while channeling self-stimulating behavior into more creative activity. Because art is naturally enjoyable for almost all children, autistic or not, they are more likely to tolerate textures and smells they might otherwise avoid when they are part of a fun art process. A child might find that he or she can actually cope with handling slimy, paste-covered strips of newspaper, for instance, when it’s part of a fun Paper Mache craft project. Repeatedly confronting the stimuli, they prefer to avoid helps to desensitize kids to them, making it more bearable when they encounter these sensations in daily life.

Art facilitates so many things. Therapist and participant working together, with the focus on art instead of one another. For those with sensory issues, therapists reshape behaviors while learning to deal with different textures, smells, and other possibly unpleasant stimuli.

Regensburg (2016) relates that the value of art therapy for those on the spectrum, for children who have difficulty in building functional skills and connecting with others can benefit from art therapy. That those children with ASD are designed differently and don’t fit into our mainstream systems. He feels that in order for art therapy to be successful, the child’s spirit and mind must be treated. He believes that a professionally trained and credentialed therapist can ‘connect’ with children in their multisensory world.

A licensed and credentialed Art Therapist has completed a degree in art and art therapy, to include –

Epp (2008) talks about the implications of art therapy explaining that most people with ASD are so disengaged from others that their mental and emotional stress can cause chronic anxiety. But, when teaching social and communication skills through art therapy, one can begin giving children the ability and opportunity to fulfill their need for friendship and companionship.

< My Thoughts > “…disengaged from others…”

At school and at home, there are posters, pages, and coloring books available to use. Sonny sometimes sits me down to color. I give him 3 pages to choose from. Then, ask him to pick the colors to use. Once he gets me ‘on task’, he walks away, checking on me periodically through his peripheral vision. This is something that seems to calm him down on those mornings when he starts pacing or doing his ‘zoomies’. It is also a form of social interaction which takes him out of his world, momentarily, maybe giving him a feeling of ‘control’ over his environment.

Also, these skills can be generalized to other environments with which many doctors, teachers, social workers, and psychologists are unfamiliar. “Children who are visual learners take in this information in a way that stays with them,” believes Epp. Through art therapy it offers a way to solve problems visually. This encourages children with autism to be less literal and concrete in self-expression, and offers a more non-threatening way to deal with emotion. Replacing the need for tantrums or acting-out behaviors because it offers acceptable means which soothes the child.

< My Thoughts > “…solve problems visually.”

I’ve found that creating visual storyboards about a book they are reading, or information students are trying to understand is extremely helpful for reluctant learners. I have also found that children with severe sensory issues may have serious problems with the smells and the feel of many art mediums; too smelly or too squishy. My Sonny, however, kept running away to the art room to touch, smell and taste the crayons kept in a big box by the door.

Squaresky (2014) states – four-year-old Greg sat next to me at the kitchen table. I took out a marker and tried to draw Cookie Monster. Unable to communicate with my son verbally, I decided to try to connect with him through art. Greg showed that he was able to learn, but his learning was mainly visual.

I drew Cookie Monster for a month or so, and being unable to draw anything more complex, I didn’t try other characters.

< My Thoughts > “…I decided to try to connect with him through art.”

When Sonny was a 9-year-old, he was moved to a new classroom. As you entered his new room, there was a bulletin board by the door. From the very first day, Sonny always stopped to pounce in greeting towards the Sesame Street characters posted there. Much as one would genuflect when entering a church. The teacher remarked to me that Sonny didn’t seem to acknowledge her or the classroom aide, but always stopped to excitedly coo and pat the gang on the wall, his welcoming friends.

At first, we couldn’t figure it out, and then we realized that he had books at home filled with those characters – Elmo, Cookie Monster, and Big Bird. Now we had a new way to connect with him. And, we were able to get that much closer to understanding how he connected to the world around him. These are his ‘best friends forever’ (BFFs)..

Mom continues, Greg watched me, saying, “Go Dabba”, and “more.” Speech appeared only in bits. After producing each new sketch with his scented markers, Greg smelled the Cookie Monsters.

At the beginning of the second month of drawing solo, I asked Greg if he wanted to draw. He picked up the marker and drew an animated Go Dabba. His drawing was full of personality, and his use of lines and expressions was more creative than anything I ever could draw.

Greg told his father Jay to write “Dear Cookie Monster’ next to the ‘Go Dabba’ drawing. We never discovered why Greg said these words. Perhaps he wanted Cookie to come for a visit? Also, we had no clue as to why Greg placed Cookie’s boots next to him (in the picture).

At age five, he had advanced beyond me! He seemed to have taken the picture of a character from his mind and reproduced it on paper.

< My Thoughts > “…advanced beyond me!”

A parent can look for opportunities to capitalize favorite characters their child may respond to. Look for your ‘teachable moments’. Children with autism seem to be far more receptive to ‘non-human’ connections. I’ve often imagined that Sonny replays his favorite dialogues from videos in his head when seeing certain images.

REFERENCES: UNIT 7-7 Who May Help? CAMS PART 4 – CREATIVE THERAPY, INTRODUCTION. a. Art Therapy

Lacour, K. (2018). The Value of Art Therapy for Those on the Autism Spectrum; the Art of Autism; Retrieved online from – https://the-art-of-autism.com/the-value-of--art-therapy-for-those-on-the-autism-spectrum/

Regensburg, E. (2016). The Value of Art Therapy for Those on the Autism Spectrum; the Art of Autism; Retrieved online from – https://the-art-of-autism.com/tag/ed-regensburg/

Rudy, L. (2020). What is the Best Treatment for Autism?; Very Well Health Online, Retrieved online from – https://www.verywellhealth.com/the-best-treatment-for-autism-4585131/

Epp, K. (2008). Outcome-Based Evaluation of a Social Skills Program Using Art Therapy & Group Therapy for Children on the Autism Spectrum; National Association of Social Workers; V30:1; p27-36.

Scope, A., & Uttley, L., et al. (2017). A qualitative review of service user & service provider perspectives on the acceptability, relative benefits, & potential harms of art therapy for people with non- psychotic mental health disorders; Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice; V90, p25-43.

Squaresky, M. (2014). A Spot on the Wall; eBook Edition.

Tubbs, J. (2007). Creative Therapy for Children with Autism, ADD, & Asperger’s: Using Artistic Creativity to Reach, Teach, & Touch Our Children; Square One Publishers, Garden City Park, N.Y.; Foreword.

Creative therapy here covers a. Art therapy, b. Dance therapy, c. Music therapy, d. Theatre therapy, e. Adventure therapy.

Tubbs (2007) talks about parents, who’ve seen moments of awareness in their children which have surprised and delighted them. When all three are synchronized, the spiritual, the body and mind we have an integrated human being, even with autism.

Your child’s spiritual nature may flash through in times of joy or interest. Children with autism can be moved by classical music or beautiful colors and encouraged to paint wonderful pictures.

With creative therapies parents can facilitate changes in their child by using many of the same techniques a therapist does, gaining momentum in weekly sessions.

< My Thoughts > “…parents can facilitate changes…”

Ask your child’s therapist for ways that you, as the parent, can extend or create ‘home’ sessions. If there is no therapist present, then try drawing the things that you liked to draw or paint at your child’s age. Or, if music or dance was your secret passion, create a little session for yourself wearing scarves, silly hats, etc. See if you can generate some interest from your child.

Rudy (2020) thinks that if your child might be interested in music, visual arts, acting or dancing then s/he may respond well to art therapies. These are out-of-pocket programs which may build skills and expand boundaries, but may be costly.

Squaresky (2014) says the slowness and expense of speech class frustrated me. So, we also tried movement therapy. Greg loved dancing and music. His music therapist, Elise wanted to help Greg find himself, develop his missing skills and understand that he controlled facial expressions.

In particular, Greg enjoyed watching himself in the mirror which covered a full wall of the church basement where he had therapy. He made faces as the therapist helped him discover emotions and how to express them.

She casually and skillfully entered his personal space to wake him up to life’s wonders. Interaction with other human beings was another objective.

Music therapy became a highlight of our lives. Greg played with instruments from all over the world as the music instructor, Jackie, interacted with him.

a. Art therapy

Scope, et al. (2017) reported that art therapy is considered to be an acceptable treatment for the majority of respondents. Saying that art therapy can involve using painting, clay work, and other creative visual art-making art forms; including creative digital media. There is no definitive criterion for those routinely referred for this therapy, according to these authors. The populations considered here were non-psychotic respondents with anxiety, depression and stress management issues; plus, art therapy is suggested to reduce the person’s isolation, due to autism.

Art therapy in this study is effective in a variety of settings and for a range of populations. In most situations the art therapy was delivered in a group setting where respondents felt that relationships with other members were established. Usually, participants and/or their parents felt that the time invested in art therapy was most helpful. When the therapist examined the result of their art-making with them, they were able to express their feelings about it. Most participants were reported to have better communication through artwork and even seemed to experience increased pride in expressing their thoughts and feelings through their art.

Lacour (2018) learned that Grant’s compulsive paper-tearing habit was turned into creating beautiful collages. Channeling ‘non-functioning’, stimming behavior into a creative outlet. People with autism often think in pictures. Art therapy seems to be a perfect fit for those with autism, she believes.

One of the most common goals in art therapy is to increase tolerance for unpleasant stimuli, while channeling self-stimulating behavior into more creative activity. Because art is naturally enjoyable for almost all children, autistic or not, they are more likely to tolerate textures and smells they might otherwise avoid when they are part of a fun art process. A child might find that he or she can actually cope with handling slimy, paste-covered strips of newspaper, for instance, when it’s part of a fun Paper Mache craft project. Repeatedly confronting the stimuli, they prefer to avoid helps to desensitize kids to them, making it more bearable when they encounter these sensations in daily life.

Art facilitates so many things. Therapist and participant working together, with the focus on art instead of one another. For those with sensory issues, therapists reshape behaviors while learning to deal with different textures, smells, and other possibly unpleasant stimuli.

Regensburg (2016) relates that the value of art therapy for those on the spectrum, for children who have difficulty in building functional skills and connecting with others can benefit from art therapy. That those children with ASD are designed differently and don’t fit into our mainstream systems. He feels that in order for art therapy to be successful, the child’s spirit and mind must be treated. He believes that a professionally trained and credentialed therapist can ‘connect’ with children in their multisensory world.

A licensed and credentialed Art Therapist has completed a degree in art and art therapy, to include –

- art therapeutic techniques

- psychopathology

- patient assessment/diagnosis

- cultural diversity issues

- legal/ethical practice issues; plus meeting professional standards and regulations.

Epp (2008) talks about the implications of art therapy explaining that most people with ASD are so disengaged from others that their mental and emotional stress can cause chronic anxiety. But, when teaching social and communication skills through art therapy, one can begin giving children the ability and opportunity to fulfill their need for friendship and companionship.

< My Thoughts > “…disengaged from others…”

At school and at home, there are posters, pages, and coloring books available to use. Sonny sometimes sits me down to color. I give him 3 pages to choose from. Then, ask him to pick the colors to use. Once he gets me ‘on task’, he walks away, checking on me periodically through his peripheral vision. This is something that seems to calm him down on those mornings when he starts pacing or doing his ‘zoomies’. It is also a form of social interaction which takes him out of his world, momentarily, maybe giving him a feeling of ‘control’ over his environment.

Also, these skills can be generalized to other environments with which many doctors, teachers, social workers, and psychologists are unfamiliar. “Children who are visual learners take in this information in a way that stays with them,” believes Epp. Through art therapy it offers a way to solve problems visually. This encourages children with autism to be less literal and concrete in self-expression, and offers a more non-threatening way to deal with emotion. Replacing the need for tantrums or acting-out behaviors because it offers acceptable means which soothes the child.

< My Thoughts > “…solve problems visually.”

I’ve found that creating visual storyboards about a book they are reading, or information students are trying to understand is extremely helpful for reluctant learners. I have also found that children with severe sensory issues may have serious problems with the smells and the feel of many art mediums; too smelly or too squishy. My Sonny, however, kept running away to the art room to touch, smell and taste the crayons kept in a big box by the door.

Squaresky (2014) states – four-year-old Greg sat next to me at the kitchen table. I took out a marker and tried to draw Cookie Monster. Unable to communicate with my son verbally, I decided to try to connect with him through art. Greg showed that he was able to learn, but his learning was mainly visual.

I drew Cookie Monster for a month or so, and being unable to draw anything more complex, I didn’t try other characters.

< My Thoughts > “…I decided to try to connect with him through art.”

When Sonny was a 9-year-old, he was moved to a new classroom. As you entered his new room, there was a bulletin board by the door. From the very first day, Sonny always stopped to pounce in greeting towards the Sesame Street characters posted there. Much as one would genuflect when entering a church. The teacher remarked to me that Sonny didn’t seem to acknowledge her or the classroom aide, but always stopped to excitedly coo and pat the gang on the wall, his welcoming friends.

At first, we couldn’t figure it out, and then we realized that he had books at home filled with those characters – Elmo, Cookie Monster, and Big Bird. Now we had a new way to connect with him. And, we were able to get that much closer to understanding how he connected to the world around him. These are his ‘best friends forever’ (BFFs)..

Mom continues, Greg watched me, saying, “Go Dabba”, and “more.” Speech appeared only in bits. After producing each new sketch with his scented markers, Greg smelled the Cookie Monsters.

At the beginning of the second month of drawing solo, I asked Greg if he wanted to draw. He picked up the marker and drew an animated Go Dabba. His drawing was full of personality, and his use of lines and expressions was more creative than anything I ever could draw.

Greg told his father Jay to write “Dear Cookie Monster’ next to the ‘Go Dabba’ drawing. We never discovered why Greg said these words. Perhaps he wanted Cookie to come for a visit? Also, we had no clue as to why Greg placed Cookie’s boots next to him (in the picture).

At age five, he had advanced beyond me! He seemed to have taken the picture of a character from his mind and reproduced it on paper.

< My Thoughts > “…advanced beyond me!”

A parent can look for opportunities to capitalize favorite characters their child may respond to. Look for your ‘teachable moments’. Children with autism seem to be far more receptive to ‘non-human’ connections. I’ve often imagined that Sonny replays his favorite dialogues from videos in his head when seeing certain images.

REFERENCES: UNIT 7-7 Who May Help? CAMS PART 4 – CREATIVE THERAPY, INTRODUCTION. a. Art Therapy

Lacour, K. (2018). The Value of Art Therapy for Those on the Autism Spectrum; the Art of Autism; Retrieved online from – https://the-art-of-autism.com/the-value-of--art-therapy-for-those-on-the-autism-spectrum/

Regensburg, E. (2016). The Value of Art Therapy for Those on the Autism Spectrum; the Art of Autism; Retrieved online from – https://the-art-of-autism.com/tag/ed-regensburg/

Rudy, L. (2020). What is the Best Treatment for Autism?; Very Well Health Online, Retrieved online from – https://www.verywellhealth.com/the-best-treatment-for-autism-4585131/

Epp, K. (2008). Outcome-Based Evaluation of a Social Skills Program Using Art Therapy & Group Therapy for Children on the Autism Spectrum; National Association of Social Workers; V30:1; p27-36.

Scope, A., & Uttley, L., et al. (2017). A qualitative review of service user & service provider perspectives on the acceptability, relative benefits, & potential harms of art therapy for people with non- psychotic mental health disorders; Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice; V90, p25-43.

Squaresky, M. (2014). A Spot on the Wall; eBook Edition.

Tubbs, J. (2007). Creative Therapy for Children with Autism, ADD, & Asperger’s: Using Artistic Creativity to Reach, Teach, & Touch Our Children; Square One Publishers, Garden City Park, N.Y.; Foreword.

b. Dance therapy

Dance/Movement Therapy – Hildebrandt, et al. (2016) looked at a randomized controlled study of 78 participants, between the ages of 14 and 65 years; reflecting the broad autism spectrum. They did screen and omit those with more severe symptoms and those who could not speak. The program was lead by two female dance therapists providing ten weekly sessions and a 6-month follow-up.

They decided that the participants in the treatment program did not show significantly different symptom reduction for any specific symptoms. But, ASD kids did seem to show an increased empathy and self-awareness. Thus, the authors felt that body-oriented therapy for those with ASD could improve, when and if, the participant was ‘mirroring’ with a non-autistic partner.

Sharing a poem that one of the female participants (2016) wrote which she said reflected her experience in the program.

We Dance

We dance.

Everything is dance,

So one says.

Even atoms

Swing and dance.

Electrons circle around protons and neutrons.

Everything swings, all is in harmony.

Only this way

The world is kept in an equilibrium

It is an ancient law.

< My Thoughts > “…We dance…”

This poem seems to reflect the link of movement therapy to – thoughtful learning, ability to focus outside oneself, positive self-perception; freedom of movement, expression, and emotion. Although the literature ‘reflects’ (no pun intended) that a person with autism learning through ‘mirror responses’ may be the exception to the rule. I wanted to share what ‘mirroring’ with a non-autistic partner’ may mean and just what a complex expectation it is.

Du & Greer (2014) tell us that imitation is regarded as a critical learning milestone in child development. The ‘mirror’ has long been considered an indispensable tool to direct imitation in dance training. Studies of brain imaging shows that learning face-to-face, or ‘mirror’ image, requires a higher order of responding/thinking. So, when a child reverses motor imitation by completing a motion which is the opposite of their perspective that is regarded as a milestone of cognitive development. For this reason, Du & Greer question whether children with developmental delays can learn to imitate from ‘mirror response’ training, and/or face-to-face training (such as they would in a Dance Program).

Another example they give of a ‘mirror response’ – the experimenter would raise her right hand, expecting the participant to raise his left hand (a ‘mirror response’). But if the participant raises his right hand, this would be a non-mirror response. This ‘mirror response’ learning ability would be expected in other settings as well, if the child has mastered this learning technique. For instance, ‘mirror’ cueing arm movement so that the child’s arm can later respond to a necessary motor function or skill involving arm motion; like raising arms to bathe or put on a shirt.

Davide-Rivera, J. (2013) danced to her grandparents Pianola in their living room. It played music all on its own; it was like magic. I could twirl round and round for hours to the velvety music that filled the room – and I did.

“She has ballerina feet, Grandma said, “look at her twirl, she’s a natural.” And so, off to ballet class I went. When I was dancing, and twirling, and listening to the music, I could drown the world out.

An intense focus allowed me to dance without mistake, because I could not tolerate mistakes. Everything had to be perfect; that is, perfect the way I saw perfect. The only problem was I wanted to dance alone.

Mastrominico, et al. (2018) declares that dance movement therapists have long used kinesthetic empathy to describe the experience of experiencing through bodily sensation by attending to internal reactions and sensations when mirroring or observing the other’s movements. This is often the first step in establishing empathy and emotional self-awareness.

In this study, they examine the effects of empathy on autistic adults when experiencing dance movement therapy (DMT). Empathy was measured with a Cognitive & Emotional Empathy Questionnaire (CEEQ). The hope was that dance movement would address the sensory and/or motor challenge which may interfere with emotional regulation, social engagement, and the development of social competency.

Dance movement therapists help the person connect others movements with their own bodily sensations, and consequently with their emotions. Some self-reported successfully experiencing more self-awareness, social interaction, decrease in unwanted repetitive behavior, and a sense of physical and emotional well-being. Dance therapists expressed that they also worked with those undergoing depression, anxiety, chronic pain, eating disorders, and Parkinson disease.

Colson (2010) recalled, Garry and I would dance with Max as we listened to pop rock and country western music. We loved to hold Max, look at him, drink him in like a sweet elixir.

Max was always looking up, drawn to the skylights in our home. As we danced, his eyes would widen as the lacey blue of his irises would overtake his pupils. “Skylight,” we would whisper.

Her friend Patti often told her, “Max is a gift. These children are a gift.” True, there are no ordinary days in our lives, Max and me. I don’t want to miss that open window. So right now, I’m going to dance with my son.

A Dance/Movement Therapist must be certified and licensed verifying that s/he have studied, along with creative dance movement, the study of the following –

The Movement Specialist adds to all the above strategies, plus being skilled at the following, which bring about optimal –

< My Thoughts > **Remember… As well as creating a practice or program, the principal must meet all qualifying professional standards, certification, and licensing. It’s up to you to find out if they do.

Dance/Movement Therapy – Hildebrandt, et al. (2016) looked at a randomized controlled study of 78 participants, between the ages of 14 and 65 years; reflecting the broad autism spectrum. They did screen and omit those with more severe symptoms and those who could not speak. The program was lead by two female dance therapists providing ten weekly sessions and a 6-month follow-up.

They decided that the participants in the treatment program did not show significantly different symptom reduction for any specific symptoms. But, ASD kids did seem to show an increased empathy and self-awareness. Thus, the authors felt that body-oriented therapy for those with ASD could improve, when and if, the participant was ‘mirroring’ with a non-autistic partner.

Sharing a poem that one of the female participants (2016) wrote which she said reflected her experience in the program.

We Dance

We dance.

Everything is dance,

So one says.

Even atoms

Swing and dance.

Electrons circle around protons and neutrons.

Everything swings, all is in harmony.

Only this way

The world is kept in an equilibrium

It is an ancient law.

< My Thoughts > “…We dance…”

This poem seems to reflect the link of movement therapy to – thoughtful learning, ability to focus outside oneself, positive self-perception; freedom of movement, expression, and emotion. Although the literature ‘reflects’ (no pun intended) that a person with autism learning through ‘mirror responses’ may be the exception to the rule. I wanted to share what ‘mirroring’ with a non-autistic partner’ may mean and just what a complex expectation it is.

Du & Greer (2014) tell us that imitation is regarded as a critical learning milestone in child development. The ‘mirror’ has long been considered an indispensable tool to direct imitation in dance training. Studies of brain imaging shows that learning face-to-face, or ‘mirror’ image, requires a higher order of responding/thinking. So, when a child reverses motor imitation by completing a motion which is the opposite of their perspective that is regarded as a milestone of cognitive development. For this reason, Du & Greer question whether children with developmental delays can learn to imitate from ‘mirror response’ training, and/or face-to-face training (such as they would in a Dance Program).

Another example they give of a ‘mirror response’ – the experimenter would raise her right hand, expecting the participant to raise his left hand (a ‘mirror response’). But if the participant raises his right hand, this would be a non-mirror response. This ‘mirror response’ learning ability would be expected in other settings as well, if the child has mastered this learning technique. For instance, ‘mirror’ cueing arm movement so that the child’s arm can later respond to a necessary motor function or skill involving arm motion; like raising arms to bathe or put on a shirt.

Davide-Rivera, J. (2013) danced to her grandparents Pianola in their living room. It played music all on its own; it was like magic. I could twirl round and round for hours to the velvety music that filled the room – and I did.

“She has ballerina feet, Grandma said, “look at her twirl, she’s a natural.” And so, off to ballet class I went. When I was dancing, and twirling, and listening to the music, I could drown the world out.

An intense focus allowed me to dance without mistake, because I could not tolerate mistakes. Everything had to be perfect; that is, perfect the way I saw perfect. The only problem was I wanted to dance alone.

Mastrominico, et al. (2018) declares that dance movement therapists have long used kinesthetic empathy to describe the experience of experiencing through bodily sensation by attending to internal reactions and sensations when mirroring or observing the other’s movements. This is often the first step in establishing empathy and emotional self-awareness.

In this study, they examine the effects of empathy on autistic adults when experiencing dance movement therapy (DMT). Empathy was measured with a Cognitive & Emotional Empathy Questionnaire (CEEQ). The hope was that dance movement would address the sensory and/or motor challenge which may interfere with emotional regulation, social engagement, and the development of social competency.

Dance movement therapists help the person connect others movements with their own bodily sensations, and consequently with their emotions. Some self-reported successfully experiencing more self-awareness, social interaction, decrease in unwanted repetitive behavior, and a sense of physical and emotional well-being. Dance therapists expressed that they also worked with those undergoing depression, anxiety, chronic pain, eating disorders, and Parkinson disease.

Colson (2010) recalled, Garry and I would dance with Max as we listened to pop rock and country western music. We loved to hold Max, look at him, drink him in like a sweet elixir.

Max was always looking up, drawn to the skylights in our home. As we danced, his eyes would widen as the lacey blue of his irises would overtake his pupils. “Skylight,” we would whisper.

Her friend Patti often told her, “Max is a gift. These children are a gift.” True, there are no ordinary days in our lives, Max and me. I don’t want to miss that open window. So right now, I’m going to dance with my son.

A Dance/Movement Therapist must be certified and licensed verifying that s/he have studied, along with creative dance movement, the study of the following –

- neuroanatomy

- personality development

- movement & motor behavior

- psychology of dance

- creative expression modalities

- improvisation

- group psychology & leadership

- client evaluation & supervision

The Movement Specialist adds to all the above strategies, plus being skilled at the following, which bring about optimal –

- psychophysical function

- verbal & non-verbal communication

- skilled touch techniques

- kinesthetic awareness processes

- movement observation & patterning

- client assessment & guidance.

< My Thoughts > **Remember… As well as creating a practice or program, the principal must meet all qualifying professional standards, certification, and licensing. It’s up to you to find out if they do.

c. Music therapy

Menear, et al. (2006) muse that many persons with autism avoid anything associated with exercise, gym, music or dance. Their informal observations have shown that many students with autism who have low motor skills and fitness abilities have initial difficulty traversing typical school or park playground equipment without assistance. They have poor eye-hand coordination, trouble combining multiple motor skills into one task, and any structured balance related physical activities or group activities can be difficult. But it can help if they can exercise to music.

< My Thoughts > “…exercise to music…”

The CDC advises you to give your child the opportunity to learn and sing songs from memory and exercise to music.

Landau (2013) looks into brain regions involved in movement, attention, planning and memory scans consistently showed activation when participants listened to music, these are structures that don't have to do with auditory processing itself. This means that when we experience music, a lot of other things are going on beyond merely processing sound.

< My Thoughts > “…processing sound. experiencing music…”

Music is amazing! We use a different part of the brain to understand and enjoy music. In our travel bag, we carry a small cassette player which plays classical music for Sonny when he is in stress mode, or after having a seizure. As a teacher, I have had students with autism react favorably to hearing music while they are learning a task. Shopping in stores is so much easier with Sonny if he can hear piped-in music being played.

In our classroom, there was a great student aide, but with the annoying daily habit of listening to her MP3 player through earbuds. When her student started screaming in protest about continuing to work on the puzzle in front of him, I motioned for her to put one of her earbuds in the his ear. Truly, it was like flipping a switch. He calmed down and became compliant and cooperative. Often times, discoveries like this don’t last; but, this one did. At first, the parents couldn’t believe how music changed him. But soon, they provided him with his own player and the Mariachi tunes he heard at home. Truly, music can be amazing!

Staff Writer (2015) – ‘Music’ is processed on the right side of the brain, whereas ‘speech’ is processed on the left side of the brain. Our brains process music in the same area where memories are created and stored.” When our brain attaches a positive feeling or a positive memory related to a song, the body produces ‘feel good’ hormones like ‘dopamine’ while listening to that song.

Editor (2020) – According to reports from the American Music Therapy Association (AMTA), “People with ASD often show a heightened interest and response to music, making it an excellent therapeutic tool.” They also say that a professional music therapist holds a bachelor’s degree or higher in music therapy from an accredited and approved college. In addition, most therapists may also be licensed or registered with a state licensing agency. Music therapists address behavioral, social, psychological, communicative, physical, sensory-motor, and/or cognitive functioning. This is considered to have unique outcomes.

Miller (2015) marvels that Neurologic Music Therapy (NMT) interventions are designed to re-educating the brain. Music processing involves many parts of the brain. But, because music enters the brain globally, the message has more chances of being understood, shaping the brain and changing behavior.

Children with autism often have challenges in receptive language skills. Interestingly, when listening to singing, their speech centers were active. Unlike the brains of typically developing children who in a similar study, were found NOT to have singing light up their language centers.

Neurologic music therapy is utilized to increase receptive and expressive language, increase motor planning skills, and increase cognitive skills such as sustained attention and following directions.

Neurologic Music Therapy (NMT) is somewhat new to the Music Therapy field. Based upon neuroscience research, NMT provides music in a hard-wired brain language. Thaut (2005), the developer of this research-based therapy tells us that ‘sensorimotor rehabilitation’ is defined as a therapeutic application of music to cognitive, sensory, and motor dysfunctions which are due to disease of the human nervous system. This allows the influence of music to make changes in the non-musical brain which in turn affects motor, speech, and language functions; as well as their behavior in those areas.

< My Thoughts > “…influence of music to make…”

If you wish to look into this further, the clinical text about this research-based program can be daunting, but very fascinating. Each musical session has a specific purpose. Remember ‘mirror’ cueing? Well, this is ‘rhythmically’ cueing arm movement so that the child’s arm can later rhythmically respond to a necessary motor function or skill involving arm motion; like raising arms to bathe or put on a shirt. All of these methods add to making it easier for children with autism to learn.

There is a technological device twist on this therapy also, which is an automated Neurologic Music Therapy (NMT) system where a web browser connects to the server. This software system retrieves and stores pertinent data which can design a musical game especially for a particular child.

There are games played in rounds, including turn-taking, where the child moves to the next round if all of the attempts to select music, graphics, and actions have been completed correctly. This can be used by parents and teachers to continue reinforcing the learned musical therapy and recording data by playing games at home and at school, on any device.

Thompson, et al. (2013) talks about one of the core symptoms of autism as poor engagement in social play, which impacts their future social communication. Thus, highlighting

the importance of becoming socially engaged. This study investigated a ‘family-centered’ music therapy which was found to create three key positive relationship changes. These areas were –

This included positive emotional shifts in their response toward their child. How they practically and emotionally they related to them.

The therapist in this study was said to have had the ability to create and support foundational relationship skills between the child and their family. Both family and child were given unique opportunities to develop and strengthen their relationship.

< My Thoughts > “…given unique opportunities…”

This also seems to be a unique opportunity for a family to expand these therapy sessions to include other members of the family group. To find ways to use the child’s ‘foundational’ skills in ‘follow-up’ sessions similar to those of the therapist.

Mossler, et al. (2019) examined the relational experiences ASD children had engaging with music. How the interplay of senses, emotion, and cognition were created when the body, mind, and the environment interacted. Stating that they were not sure what the child was focusing on, but that emotional regulation, organization, mentalization, and joyful engagement occurred. They say the therapist proceeds at the child’s pace, matching his or her sounds, making the session both ‘intra’ and ‘inter’ personal.

Note: In order to be certified and licensed, the musical therapist must qualify in the areas of –

Note: As well as creating a practice or program, the principal must meet all qualifying professional standards, certification, and licensing. It’s up to you to find out if they do.

REFERENCES: UNIT 7-7 Who May Help? CAMS PART 4 – b. Dance, c. Music.

Colson, E., & Colson, C. (2010). Dancing With Max: A Mother and Son Who Broke Free; eBook Edition.

Davide-Rivera, J. (2013). Twirling Naked in the Streets & No One Noticed: Growing Up with Autism; eBook Edition.

Du, L. & Greer, R. (2014). Validation of Adult Generalized Imitation (GI) & the Emergence of GI in Young Children with Autism as a Function of Mirror Training; Psychological Record; V64, p161-177.

Editor (2020). American Music Therapy Association (AMTA); Retrieved online from – https://www.musictherapy.org/

Hildebrandt, M., Koch, S., Fuchs, T. (2016). We Dance & Find Each Other: Effects of Dance/Movement Therapy on Negative Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorder; Behavioral Sciences; V6:24.

Landau, E. (2013). This Is Your Brain on Music; CNN, Retrieved online from – www.cnn.com/2013/04/15/health/brain-music-research/

Mastrominico, A., Fuchs, T., et al. (2018). Effects of Dance Movement Therapy on Adult Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial; Behavior Sciences; V8:61, p1-18.

Menear, K., Smith, S., et al. (2006). A Multipurpose Fitness Playground for Individuals with Autism; Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance.

Miller, M. (2015). Neurologic Music Therapy (NMT) & Autism; Retrieved online from – https://www.rhythmandstrings.com/post/2015/10/28/neurologic-music-therapy-and-autism/

Mossler, K., Gold, C., et al. (2019). The Therapeutic Relationship as Predictor of Change in Music Therapy with Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder; Journal of Experiential Education; V49, p2795-2809.

Staff Writer (2015). Fun Facts about Music & Your Brain; Retrieved online from –keychangesmusictherapy.com/2015/09/fun-facts-about-music-and-your-brain/

Thaut, M. H. (2005). Neurologic Music Therapy Techniques & Definitions; Rhythm: Music & the Brain; Taylor Francis Group, N.Y. & London.

Thompson, G., McFerran, K., et al. (2013). Family-centered music therapy to promote social engagement in young children with severe autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled study; Child: care, health & development; University of Melbourne, Australia.

Menear, et al. (2006) muse that many persons with autism avoid anything associated with exercise, gym, music or dance. Their informal observations have shown that many students with autism who have low motor skills and fitness abilities have initial difficulty traversing typical school or park playground equipment without assistance. They have poor eye-hand coordination, trouble combining multiple motor skills into one task, and any structured balance related physical activities or group activities can be difficult. But it can help if they can exercise to music.

< My Thoughts > “…exercise to music…”

The CDC advises you to give your child the opportunity to learn and sing songs from memory and exercise to music.

Landau (2013) looks into brain regions involved in movement, attention, planning and memory scans consistently showed activation when participants listened to music, these are structures that don't have to do with auditory processing itself. This means that when we experience music, a lot of other things are going on beyond merely processing sound.

< My Thoughts > “…processing sound. experiencing music…”

Music is amazing! We use a different part of the brain to understand and enjoy music. In our travel bag, we carry a small cassette player which plays classical music for Sonny when he is in stress mode, or after having a seizure. As a teacher, I have had students with autism react favorably to hearing music while they are learning a task. Shopping in stores is so much easier with Sonny if he can hear piped-in music being played.

In our classroom, there was a great student aide, but with the annoying daily habit of listening to her MP3 player through earbuds. When her student started screaming in protest about continuing to work on the puzzle in front of him, I motioned for her to put one of her earbuds in the his ear. Truly, it was like flipping a switch. He calmed down and became compliant and cooperative. Often times, discoveries like this don’t last; but, this one did. At first, the parents couldn’t believe how music changed him. But soon, they provided him with his own player and the Mariachi tunes he heard at home. Truly, music can be amazing!

Staff Writer (2015) – ‘Music’ is processed on the right side of the brain, whereas ‘speech’ is processed on the left side of the brain. Our brains process music in the same area where memories are created and stored.” When our brain attaches a positive feeling or a positive memory related to a song, the body produces ‘feel good’ hormones like ‘dopamine’ while listening to that song.

Editor (2020) – According to reports from the American Music Therapy Association (AMTA), “People with ASD often show a heightened interest and response to music, making it an excellent therapeutic tool.” They also say that a professional music therapist holds a bachelor’s degree or higher in music therapy from an accredited and approved college. In addition, most therapists may also be licensed or registered with a state licensing agency. Music therapists address behavioral, social, psychological, communicative, physical, sensory-motor, and/or cognitive functioning. This is considered to have unique outcomes.

Miller (2015) marvels that Neurologic Music Therapy (NMT) interventions are designed to re-educating the brain. Music processing involves many parts of the brain. But, because music enters the brain globally, the message has more chances of being understood, shaping the brain and changing behavior.

Children with autism often have challenges in receptive language skills. Interestingly, when listening to singing, their speech centers were active. Unlike the brains of typically developing children who in a similar study, were found NOT to have singing light up their language centers.

Neurologic music therapy is utilized to increase receptive and expressive language, increase motor planning skills, and increase cognitive skills such as sustained attention and following directions.

Neurologic Music Therapy (NMT) is somewhat new to the Music Therapy field. Based upon neuroscience research, NMT provides music in a hard-wired brain language. Thaut (2005), the developer of this research-based therapy tells us that ‘sensorimotor rehabilitation’ is defined as a therapeutic application of music to cognitive, sensory, and motor dysfunctions which are due to disease of the human nervous system. This allows the influence of music to make changes in the non-musical brain which in turn affects motor, speech, and language functions; as well as their behavior in those areas.

< My Thoughts > “…influence of music to make…”

If you wish to look into this further, the clinical text about this research-based program can be daunting, but very fascinating. Each musical session has a specific purpose. Remember ‘mirror’ cueing? Well, this is ‘rhythmically’ cueing arm movement so that the child’s arm can later rhythmically respond to a necessary motor function or skill involving arm motion; like raising arms to bathe or put on a shirt. All of these methods add to making it easier for children with autism to learn.

There is a technological device twist on this therapy also, which is an automated Neurologic Music Therapy (NMT) system where a web browser connects to the server. This software system retrieves and stores pertinent data which can design a musical game especially for a particular child.

There are games played in rounds, including turn-taking, where the child moves to the next round if all of the attempts to select music, graphics, and actions have been completed correctly. This can be used by parents and teachers to continue reinforcing the learned musical therapy and recording data by playing games at home and at school, on any device.

Thompson, et al. (2013) talks about one of the core symptoms of autism as poor engagement in social play, which impacts their future social communication. Thus, highlighting

the importance of becoming socially engaged. This study investigated a ‘family-centered’ music therapy which was found to create three key positive relationship changes. These areas were –

- Parent-child relationship

- Perception of the child

- Responses towards the child

This included positive emotional shifts in their response toward their child. How they practically and emotionally they related to them.

The therapist in this study was said to have had the ability to create and support foundational relationship skills between the child and their family. Both family and child were given unique opportunities to develop and strengthen their relationship.

< My Thoughts > “…given unique opportunities…”

This also seems to be a unique opportunity for a family to expand these therapy sessions to include other members of the family group. To find ways to use the child’s ‘foundational’ skills in ‘follow-up’ sessions similar to those of the therapist.

Mossler, et al. (2019) examined the relational experiences ASD children had engaging with music. How the interplay of senses, emotion, and cognition were created when the body, mind, and the environment interacted. Stating that they were not sure what the child was focusing on, but that emotional regulation, organization, mentalization, and joyful engagement occurred. They say the therapist proceeds at the child’s pace, matching his or her sounds, making the session both ‘intra’ and ‘inter’ personal.

Note: In order to be certified and licensed, the musical therapist must qualify in the areas of –

- instruction in music theory

- human growth and development

- biomedical sciences

- abnormal psychology

- disabling conditions

- patient assessment & diagnosis

- treatment plan development/implementation

- clinical evaluation/data & record keeping

Note: As well as creating a practice or program, the principal must meet all qualifying professional standards, certification, and licensing. It’s up to you to find out if they do.

REFERENCES: UNIT 7-7 Who May Help? CAMS PART 4 – b. Dance, c. Music.

Colson, E., & Colson, C. (2010). Dancing With Max: A Mother and Son Who Broke Free; eBook Edition.

Davide-Rivera, J. (2013). Twirling Naked in the Streets & No One Noticed: Growing Up with Autism; eBook Edition.

Du, L. & Greer, R. (2014). Validation of Adult Generalized Imitation (GI) & the Emergence of GI in Young Children with Autism as a Function of Mirror Training; Psychological Record; V64, p161-177.

Editor (2020). American Music Therapy Association (AMTA); Retrieved online from – https://www.musictherapy.org/

Hildebrandt, M., Koch, S., Fuchs, T. (2016). We Dance & Find Each Other: Effects of Dance/Movement Therapy on Negative Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorder; Behavioral Sciences; V6:24.

Landau, E. (2013). This Is Your Brain on Music; CNN, Retrieved online from – www.cnn.com/2013/04/15/health/brain-music-research/

Mastrominico, A., Fuchs, T., et al. (2018). Effects of Dance Movement Therapy on Adult Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial; Behavior Sciences; V8:61, p1-18.

Menear, K., Smith, S., et al. (2006). A Multipurpose Fitness Playground for Individuals with Autism; Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance.

Miller, M. (2015). Neurologic Music Therapy (NMT) & Autism; Retrieved online from – https://www.rhythmandstrings.com/post/2015/10/28/neurologic-music-therapy-and-autism/

Mossler, K., Gold, C., et al. (2019). The Therapeutic Relationship as Predictor of Change in Music Therapy with Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder; Journal of Experiential Education; V49, p2795-2809.

Staff Writer (2015). Fun Facts about Music & Your Brain; Retrieved online from –keychangesmusictherapy.com/2015/09/fun-facts-about-music-and-your-brain/

Thaut, M. H. (2005). Neurologic Music Therapy Techniques & Definitions; Rhythm: Music & the Brain; Taylor Francis Group, N.Y. & London.

Thompson, G., McFerran, K., et al. (2013). Family-centered music therapy to promote social engagement in young children with severe autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled study; Child: care, health & development; University of Melbourne, Australia.

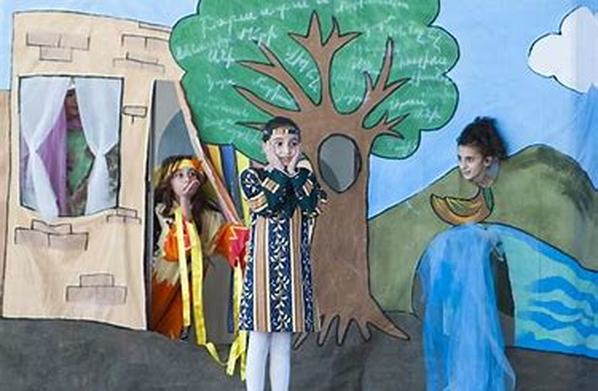

d. Theatre therapy

Corbett (2011) and her colleagues evaluated a theatrical intervention program called SENCE (Social-Emotional Neuroscience & Endocrinology) Theatre. This Theatre Therapy was designed to improve socio-emotional functioning and reduce stress in children with autism. In this study, eight children with ASD were paired with typically developing peers that served as expert models.

Because deficits in social functioning contribute to problems with anxiety in autism, performing theatre, creating video modeling extension, and social stories were thought to help these children. The group included 8 children with ASD, and 8 typically developing boys and girls; with the ages from 6 – 17 years. Inclusion required the families to attend the majority of rehearsals and performances. Each actor’s role was broken down into teachable parts to facilitate learning. The children with ASD had one-on-one behavioral support, physical prompting and social reinforcement; on stage and off.

Data was taken, with established behavioral science methods, to determine how students developed in the core areas of challenge. Areas such as – social & emotional processing, memory for faces, recognition of emotional facial expressions, theory of mind (i.e., ability to interpret your thoughts and the thoughts of others). At the end, it was felt that despite this novel intervention holding promise, they needed a much larger group with much more data before making a recommendation. They also felt that adding music to the Theatre Therapy program would have had a positive impact to the overall process.

< My Thoughts > “…the overall process…”

This current study was considered to be a success and the highlight of the treatment seemed to be the peer-mediation process. Included with that was the promise of more theatre-based approaches to advancing, maintaining, and generalizing social competence in children with ASD. No mention was made of adding music this time around, but when going on a SENCE theatre therapy website, it seems that music is part of the program.

Years later, and with different colleagues, Corbett, et al. (2017) once again investigated Theatre Therapy as an intervention for children with autism. More specifically, this time they are looking for how the social brain facilitates social cognition which consequently produces social behavior. This social behavior, it is hoped, over time and context, establishes social functioning. The study involved a group of 30 students from 8-14 years old; with a 2-month follow-up to check the effects of the therapy.

Specifically, this time they were concerned with the struggle ASD kids have with verbal and non-verbal back-and-forth social communication and social interaction. Their concern was that there would be added stress interacting with an unfamiliar peer in this large group of strangers. Also concerning was whether the ASD student could manage remembering facial information, which was an important marker for learning social skills and a target for the treatment.

Peers were trained as an ‘intentional’ model and they assisted students as they learned theatrical techniques. These were role-playing, improvisation, and play performances. There was also video-modeling which used scripted interactions to help students generalize the social behaviors they were learning.

Hall (2011) – I was really in a bad place with too many levels of unfamiliar and scary stuff going on. Diagnosed with Lupus, Mom was hospitalized practically every month and spent most of her time at home in bed. Dad was too busy and too worried about Mom to deal with my problems.

One day, I just got fed up with it all; I woke up upset and simply did not want to go to school. I was not sick; I had just had it. Everything, every day was so hard. The strain of trying to fit in and be ‘normal’ was exhausting.

My parents did not know that I still could not approach new people or make new friends. They had no clue as to the physical, mental, and emotional abuse I absorbed every day. I had never let them know that school was a constant battle for which I had no armor, no weapons, and no backup.

Toward the end of the school year, all seventh graders had to pick a short-term elective. I chose stage crew because it wasn’t academic and it looked interesting and easy. Before long, there was a job offered where someone on the stage crew would be available to help groups who rented the school’s 500 seat theater for amateur productions and other events.

As soon as I heard about the job, I wanted it. I learned to go up on the catwalks, how to handle scenery and curtain cues, and how to work all the other backstage mechanics that make a show run smoothly. I doubt kids are allowed to do those kinds of things today, because of the liability issue, but back then, I ran the theatre.

I loved my job in the theater, and I got along well with the clients using the space. I enjoyed my first real taste of independence. I rode my bike everywhere, took the bus, and worked a real job. Life was good.

Baiguerra (2018) believes that moving to London from Australia to train with a theatre company there in physical theater as a performer and folk musician fulfilled her career and life choices. Before an Asperger’s diagnosis, she says that she wasn’t always able to make sense of things that everyone else found straightforward. That her powerful journey also included feeling of fear, loneliness and shame, which is projected onto many people with a neurodiversity and/or radically different disabilities.

A Theatre Therapy program specialist is – the person or persons leading the program. They should be Registered Drama Therapists, whose training prepares them to help participants tell their stories, express their feelings, solve problems, set goals, explore interpersonal relationship skills and strengthen their own life roles.

A Registered Drama Therapist (RDT) has completed master’s level coursework in psychology and drama therapy. Also, he or she would have experience in theatre and have had a supervised internship and work experience in the field. RDTs are board certified by the North American Drama Therapy Association. As well as creating a drama therapy practice, one must meet all professional standards, certification, and licensing.

**Remember… As well as creating a practice or program, the principal must meet all qualifying professional standards, certification, and licensing. It’s up to you to find out if they do.

Corbett (2011) and her colleagues evaluated a theatrical intervention program called SENCE (Social-Emotional Neuroscience & Endocrinology) Theatre. This Theatre Therapy was designed to improve socio-emotional functioning and reduce stress in children with autism. In this study, eight children with ASD were paired with typically developing peers that served as expert models.

Because deficits in social functioning contribute to problems with anxiety in autism, performing theatre, creating video modeling extension, and social stories were thought to help these children. The group included 8 children with ASD, and 8 typically developing boys and girls; with the ages from 6 – 17 years. Inclusion required the families to attend the majority of rehearsals and performances. Each actor’s role was broken down into teachable parts to facilitate learning. The children with ASD had one-on-one behavioral support, physical prompting and social reinforcement; on stage and off.

Data was taken, with established behavioral science methods, to determine how students developed in the core areas of challenge. Areas such as – social & emotional processing, memory for faces, recognition of emotional facial expressions, theory of mind (i.e., ability to interpret your thoughts and the thoughts of others). At the end, it was felt that despite this novel intervention holding promise, they needed a much larger group with much more data before making a recommendation. They also felt that adding music to the Theatre Therapy program would have had a positive impact to the overall process.

< My Thoughts > “…the overall process…”

This current study was considered to be a success and the highlight of the treatment seemed to be the peer-mediation process. Included with that was the promise of more theatre-based approaches to advancing, maintaining, and generalizing social competence in children with ASD. No mention was made of adding music this time around, but when going on a SENCE theatre therapy website, it seems that music is part of the program.

Years later, and with different colleagues, Corbett, et al. (2017) once again investigated Theatre Therapy as an intervention for children with autism. More specifically, this time they are looking for how the social brain facilitates social cognition which consequently produces social behavior. This social behavior, it is hoped, over time and context, establishes social functioning. The study involved a group of 30 students from 8-14 years old; with a 2-month follow-up to check the effects of the therapy.

Specifically, this time they were concerned with the struggle ASD kids have with verbal and non-verbal back-and-forth social communication and social interaction. Their concern was that there would be added stress interacting with an unfamiliar peer in this large group of strangers. Also concerning was whether the ASD student could manage remembering facial information, which was an important marker for learning social skills and a target for the treatment.

Peers were trained as an ‘intentional’ model and they assisted students as they learned theatrical techniques. These were role-playing, improvisation, and play performances. There was also video-modeling which used scripted interactions to help students generalize the social behaviors they were learning.

Hall (2011) – I was really in a bad place with too many levels of unfamiliar and scary stuff going on. Diagnosed with Lupus, Mom was hospitalized practically every month and spent most of her time at home in bed. Dad was too busy and too worried about Mom to deal with my problems.

One day, I just got fed up with it all; I woke up upset and simply did not want to go to school. I was not sick; I had just had it. Everything, every day was so hard. The strain of trying to fit in and be ‘normal’ was exhausting.

My parents did not know that I still could not approach new people or make new friends. They had no clue as to the physical, mental, and emotional abuse I absorbed every day. I had never let them know that school was a constant battle for which I had no armor, no weapons, and no backup.

Toward the end of the school year, all seventh graders had to pick a short-term elective. I chose stage crew because it wasn’t academic and it looked interesting and easy. Before long, there was a job offered where someone on the stage crew would be available to help groups who rented the school’s 500 seat theater for amateur productions and other events.

As soon as I heard about the job, I wanted it. I learned to go up on the catwalks, how to handle scenery and curtain cues, and how to work all the other backstage mechanics that make a show run smoothly. I doubt kids are allowed to do those kinds of things today, because of the liability issue, but back then, I ran the theatre.

I loved my job in the theater, and I got along well with the clients using the space. I enjoyed my first real taste of independence. I rode my bike everywhere, took the bus, and worked a real job. Life was good.

Baiguerra (2018) believes that moving to London from Australia to train with a theatre company there in physical theater as a performer and folk musician fulfilled her career and life choices. Before an Asperger’s diagnosis, she says that she wasn’t always able to make sense of things that everyone else found straightforward. That her powerful journey also included feeling of fear, loneliness and shame, which is projected onto many people with a neurodiversity and/or radically different disabilities.

A Theatre Therapy program specialist is – the person or persons leading the program. They should be Registered Drama Therapists, whose training prepares them to help participants tell their stories, express their feelings, solve problems, set goals, explore interpersonal relationship skills and strengthen their own life roles.

A Registered Drama Therapist (RDT) has completed master’s level coursework in psychology and drama therapy. Also, he or she would have experience in theatre and have had a supervised internship and work experience in the field. RDTs are board certified by the North American Drama Therapy Association. As well as creating a drama therapy practice, one must meet all professional standards, certification, and licensing.

**Remember… As well as creating a practice or program, the principal must meet all qualifying professional standards, certification, and licensing. It’s up to you to find out if they do.

e. Adventure Therapy

Note: Because it has some similarities to Theatre Therapy, I would like to add Adventure Therapy.

Adventure Therapy

Karoff, et al. (2017) collected data on an Adventure Therapy camp from both children with ASD and the Student Anchors (trained teen mentors) placed throughout the sessions. The conception of this program came about because these professionals felt that school systems tried to integrate ASD youth into mainstream classrooms without the social-interaction experience.

They understood that there weren’t any interventions in place to keep ASD youth from struggling socially and feeling excluded from social networks. Thus, they wanted to give them an experience to help them adjust. These investigators wanted to address the general communication distress which the complexity of the social landscape seemed to create. And they wanted to deal with the ASD student’s possible increased awareness or concern over their social competence, when facing peers.

In conclusion, everyone felt that the Adventure Therapy experience gave students a deeper understanding of the shift in the process of mainstreaming to an inclusion classroom with their non-disabled peers. While at the same time, they were giving this group of ASD individuals the opportunity to reflect on the process of learning about ‘here-and-now’ behaviors and emotions. As well as, giving students a chance to spend time interacting with their non-disabled peers, beyond the school environment.

< My Thoughts > “…‘here-and-now’ behaviors and emotions…”

This therapy’s philosophy resonated with me because the ‘here-and-now’ approach was partially the premise of my Master's Thesis in Reading which was titled – Start Them Where They Are: A Reading Program for All Ages. I will admit that it took several attempts before the powers-that-be thought it was okay to be so ‘forward’ thinking. After all, foundational learning comes from studying by rote, starting on page one, at level one, moving through reading levels, and so on. This, however, is not always the best approach.

Hall (2011) had to worry about going to 9th grade at Windward. I was once thought to be low functioning on the autism scale. Now, all I had to worry about was going to a new summer camp; Gold Arrow Camp. It was disheartening to plummet into yet another unfamiliar situation where I had no friends or comfort and consequently felt alone and out-of-place. I guess I still came across as different, even with all the progress I had made.

The last week of July, our age group went on a five-day survival-training trip up a mountain. Before cell phones, we had no radios with which to keep in touch, we were alone out there. We hiked into the wilderness on a sixty-mile trail.

That hike was one of the most beautiful experiences of my life. I had never seen natural running water before or the open-air splendor of the mountains. It was pretty much a solitary enjoyment. I carried a seventy-pound backpack for five days, a major accomplishment for me.

When we got back from that hike, I wanted to crawl under a rock by myself whenever somebody wanted to talk to me. So, I chose solitary activities – sailing, rifle shooting, horseback riding, motorbike riding – and I avoided the group activities as much as I could. I also stayed in the cabin a little longer, and when in doubt, I went sailing.

I loved sailing. It took me longer to pick it up because I had a lot of trouble with things like tying figure-eight knots. Tying had always been a problem for me. The instructor took extra time with me and finally I got it.

Once I learned how to sail, I went out on Castaic Lake pretty much every day I could during the entire six weeks of camp. It was the best feeling in the world. I got really good at sailing.

I loved showing other people things I knew, like sailing. It made me feel more confident. It made me feel even better that they wanted and accepted my help. Suddenly, I had a new way to relate to people. By the end of summer, I was sailing 16-foot catamarans, teaching others how to sail them, and sometime skippering other campers. What a great feeling!

Karoff, et al. (2017) present one model, a peer-mediated ‘adventure therapy’ program of high school students with ASD. This peer-to-peer support program, taught in a natural setting, was said to improve social skills of all participants. The two overreaching ASD program goals were (a) increased socialization and (b) greater independence. Throughout the program, anxiety, confusion, and meltdowns were dealt with by ‘peer-buddies’ who were referred to as ‘anchors’ in the program. In conclusion, they say all programs such as this should be evaluated for a deeper understanding of their effectiveness.

Ekman & Hiltunen (2015) suggest that people with ASD have difficulties with ‘theory of mind’ (ToM). The concept that other people have thoughts, ideas, or opinions which differ from the ones they are having. Also, many with ASD do not have the empathetic abilities of feeling ‘sorry’ for someone.

But, during their ‘real-world’ outdoor experience, the participants increasingly began understanding another’s perspective. They started predicting and looking for signs of how others were communicating their needs. Also, they noticed less avoidance and anxiety behavior. Because of this, observers felt that there was an improvement in the children’s overall cognitive functioning. In other words, they seemed more ‘aware’ somehow.

< My Thoughts > “…about Adventure and Theatre Therapy…”

Both Adventure Therapy and Theatre Therapy are ‘trending’, currently. Even more reason to be cautious, asking for credentials and taking precautions to protect your child. It seems that the Adventure Therapy programs are conducted from a base camp of some kind; a ranch, a recreational campsite, or the like. Finding a program that specializes in children or teens with autism would be another challenge. Some summer adventure camp programs do have ‘family’ sessions. As for the staff conducting the program, they may be volunteers, public school teachers or those in the healthcare profession, but it would take some searching to find a licensed and accredited program with a vetted staff.

REFERENCES: UNIT 7-7 Who May Help? CAMS PART 4 – d. Theatre Therapy e. Adventure Therapy

Baiguerra, T. (2018). My Brain Isn’t Broken; Retrieved online from – TED Talks London.

Corbett, B., Gunther, J., et al. (2011). Theatre as Therapy for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder; Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders; V41, p505-511.

Corbett, B., Key, A., et al. ( (2017). Improvement in Social Competence Using a Randomized Trial of a Theatre Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder; Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders; V46, p658-672.

Ekman, E., & Hiltunen, A. (2015). Modified CBT using visualization for ASD anxiety & avoidance behavior; Scandinavian Journal of Psychology; V56, p641-648.

Hall, J. (2011). Am I Still Autistic: How a Low-Functioning, Slightly Retarded Toddler Became the CEO of a Multi-Million Dollar Corporation?; eBook Edition.

Karoff, M., Tucker, A., et al. (2017). Infusing a Peer-to-Peer Support Program with Adventure Therapy for Adolescent Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder; Journal of Experiential Education; V40:4, p394-408.

Note: Because it has some similarities to Theatre Therapy, I would like to add Adventure Therapy.

Adventure Therapy

Karoff, et al. (2017) collected data on an Adventure Therapy camp from both children with ASD and the Student Anchors (trained teen mentors) placed throughout the sessions. The conception of this program came about because these professionals felt that school systems tried to integrate ASD youth into mainstream classrooms without the social-interaction experience.

They understood that there weren’t any interventions in place to keep ASD youth from struggling socially and feeling excluded from social networks. Thus, they wanted to give them an experience to help them adjust. These investigators wanted to address the general communication distress which the complexity of the social landscape seemed to create. And they wanted to deal with the ASD student’s possible increased awareness or concern over their social competence, when facing peers.