Know Autism – Know Your Child: with < My Thoughts > by Sara Luker 2023

UNIT 2 – Why Is It Autism?

UNIT 2 – INTRODUCTION

UNIT 2 – CHAPTER 1 – Diagnosis & DSM-5 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition; published in 2013 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA)

UNIT 2 – CHAPTER 2 – Denial & Misdiagnosis

UNIT 2 – CHAPTER 3 – Doctors & Direction Unit 1 – REFERENCES

UNIT 2 – REFERENCES

UNIT 2 – APPENDICES:

APPENDIX A SCREENING ASSESSMENTS

APPENDIX B LATEST 2022 FINDINGS

APPENDIX C DEVELOPMENTAL SCREENINGS

PLEASE READ DISCLAIMER –

UNIT 2 – Why Is It Autism?

UNIT 2 – INTRODUCTION

UNIT 2 – CHAPTER 1 – Diagnosis & DSM-5 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition; published in 2013 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA)

UNIT 2 – CHAPTER 2 – Denial & Misdiagnosis

UNIT 2 – CHAPTER 3 – Doctors & Direction Unit 1 – REFERENCES

UNIT 2 – REFERENCES

UNIT 2 – APPENDICES:

APPENDIX A SCREENING ASSESSMENTS

APPENDIX B LATEST 2022 FINDINGS

APPENDIX C DEVELOPMENTAL SCREENINGS

PLEASE READ DISCLAIMER –

UNIT 2 – Why Is It Autism?

INTRODUCTION – WHY IS IT AUTISM?

The resounding theme throughout this writing is to ‘know autism and know your child’. There are no blood tests to identify an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnosis. Instead, doctors must look at the patient’s developmental and biological history to begin choosing a path to diagnosis. There are many observational types of developmental screening tests used by professionals in the field. Professionals such as the Developmental Pediatrician, Child Neurologist, Child Psychologist, Speech / Language Pathologist, or qualified Occupational Therapist.

Clinicians are looking for unusual patterns in the individual’s communication, social interaction, interests and activities, as compared to a typically developing person. Autism identification is made when a qualified clinician makes a diagnosis which meets the standards as defined in the latest Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition, DSM-5 (2013). Candidly doctors have said, “With all of the individual differences and seemingly constantly changing patterns we see a child go through developmentally, we often have difficultly deciding how to move forward. And then, if we do decide that the individual may be on the Autism Spectrum, difficultly deciding what is the clinically appropriate next step.”

So much of the child’s diagnosis depends on parents and caregiver reporting. In mild cases of Autism, parents aren’t always aware that anything is truly wrong with their child, even when compared to their siblings. Autism awareness has helped the world understand the importance of parent reporting, early identification, and early intervention.

Physicians now have more training than in the past, but still most screening tests rely heavily upon parent and caregiver reporting. ‘Denial’ still continues to loom large everywhere. Then, there is always a chance for ‘no’ diagnosis or ‘misdiagnosis’, due to the worldwide lack of available clinically trained developmental specialists; plus ‘gaps’ in critical information from parents and providers.

The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) declares that “developmental screening for autism can be done by a number of professionals in health care, community, and school settings.’ Suggesting that families, depending on the child’s age, start with the current healthcare provider or school professionals.

< My Thoughts > “…depending on the child’s age.”

So much of the child’s diagnosis depends on the accuracy of parents and caregiver reporting. Autism ‘signs and symptoms’ fall on a spectrum, from mild to profound. As an individual’s age changes, as settings change, and as there are available interventions, the child’s ‘needs’ may change. One may move up or down the autism trajectory. So, consider ‘who’ the person is, their age (infant, toddler, young child, school-age child, adolescent, young adult, older adult) and their ‘needs’ at the time, before finding the appropriate professional to consult. Ask for corresponding ‘service’ referrals to qualified persons.

Becerra-Culqui, et al. (2018) believe that specific developmental concerns can distinguish between an early versus a later diagnosis of ASD. In the United States, legislation is in place to address the needs of children with developmental delays before the age of 3 years; along with an early intervention program available under Part C of IDEA (the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) Part C, stating that the families are to receive services, regardless of their ability to pay). Early diagnosis can lead to the early intervention, essential for minimizing delays and optimizing development. Parents are more often able to identify nonverbal social communication delays leading to an ASD diagnosis, before the age of three; although speech and language delay is no longer listed as a necessary ‘primary feature’ in the 2013, DSM-5.

Consistently, parents were asked, “Who was the first person to mention the possibility of your young child having ASD?” Response was – “the first person was a parent, or other family member, and/or pediatrician.” As compared to children who were later diagnosed at 3-5 years, generally by the child’s pediatrician or classroom teacher.

Concerns with the timing of the diagnosis may determine a choice of starting with a ‘short-term’ intervention, as well as deciding what the family should do to support the child while they waited.

< My Thoughts > “…while they waited…”

The impact of the symptoms on the child and the family may also be a deciding factor, as to the timing and the nature of the interventions considered; as well as the actions taken while they waited. A ‘short-term’ intervention may be needed immediately, especially if the child is at risk for hurting self, or others.

Hart (2011) exclaims – We brought Ewan home on a Saturday afternoon, and by Monday I was on the phone with the pediatrician’s office. I explained to the doctor that Ewan would stare up at me with those wide dark eyes for hours on end. He would stare at the ceiling fan, the blinds, the shadows on the wall, anything but the backs of his eyelids. The receptionist said, “Well, you must have eaten a lot of fish when you were pregnant with that little one.” “What?” “You think the reason why he’s not sleeping is because he’s smart?”

The next few weeks were a bit of a blur, as it is for all new mothers and fathers. My husband was not in a position to take a few weeks off, so he was back to work already, and this mother was stuck at home with our sleepless wonder. My only comfort was consulting a pediatrician’s guide to raising infants and toddlers.

Pouring over the book chapters again and again, there was nothing that came even remotely close to explaining or describing my son. So, I bought a second, and a third book. Nothing there either. The answers wouldn’t come from a book; I was truly on my own with this child.

< My Thoughts > “…I was truly on my own with this child.”

For so long, parents and pediatricians both have had an almost impossible task of unraveling the mystery of each child’s autism. Then, when a staff member makes an unprofessional comment (you must have eaten a lot of fish when you were pregnant…), that just adds to the confusion.

Each child presents autism in an individual way. That is why some have compared autism to ‘snowflakes’, because as no two snowflakes are said to be alike, no two cases of autism are ever alike. Hopefully, with the many references in this book, you will find your ‘truth’, see your ‘trajectory’, and find a ‘visible path’ to take.

So many times, in the past, clinicians found children with autism have also had learning and digestive difficulties. But a child with learning disabilities and/or digestive difficulties may or may NOT have autism. The same holds true for believing that many other disorders also signal ‘autism’ – such as mental deficits, speech or hearing difficulties, weak immune systems, and so on. There are other conditions which may have ‘autism-like’ symptoms. Know your child. Know their autism.

Cettina (2017) “A label changed our life.” For some, the autism ‘label’ is a godsend. For others, it is stigmatizing and just one professional’s opinion – and sometimes even a probable misdiagnosis. Those in favor of ‘labeling’ point out that the best treatment starts early. The sooner that you pinpoint (label) your child’s needs, the faster you can find the necessary support or even medication. There is also relief in being able to ‘blame’ a medical diagnosis. There is relief in getting help.

Cademy (2013) confides that the subject of ‘labels’ is alluded to in many books and may have been overlooked by those new to Autism. Labels can be scary, but usually your child’s Asperger’s Syndrome (AS) label can be removed from records when appropriate, as they reach a certain age. Check the laws for your state on this, if you have ‘early labeling’ concerns.

Merchent (2007) shares – I was afraid an ‘autism’ label would influence people’s expectations of my son and his behavior. Afraid that it would become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

At this point in time, I had taken Clay to anyone I thought might be able to help –

- Two pediatricians

- Osteopath

- Homeopath

- Ear, nose, and throat specialist (ENT)

- Allergist

- Naturopath

- Emotional healer

- Herbalist

- Speech therapist

- Occupational therapist

- Immune disorder specialist

The osteopath and herbalist were the only ones who seemed to be helping. All the others said they could help, but we didn’t see any results.

With the strict allergy diet, and removal of incoming aluminum, Clay’s head-banging and toe-walking had almost stopped, but he still wasn’t speaking. He was cranky, sickly, and not sleeping well.

< My Thoughts > “…strict allergy diet, and removal of incoming aluminum…”

Allergy diets and removal of incoming aluminum are NOT considered to be ‘evidence-based’ interventions to symptoms of autism. They are considered to be Complementary & Alternative Medicine (CAMs).

Note: More about Complementary & Alternative Medicine (CAMs) in UNIT 7 chapters.

Park (2015) provides us with the latest information from scientists zeroing in on the best ways to diagnose autism. Genetic testing can be done which specifically looks at abnormalities in the chromosomes. This extensive genetic testing is called whole-exome sequencing. But scientist Scherer says that “…if we use only one technology, we could miss some important information.” Therefore, they choose to also use brain scans, and conventional behavioral evaluations, along with genetic testing,

Some believe that ‘behavioral’ evaluative testing can be the first step because working with genetic counselors to do genetic testing first, can be very expensive. The final necessary step is to obtain a more detailed evaluation. Children, more than ever are showing complex autism symptoms. Professionals feel that it will take as many factors as possible to accurately identify and begin the most appropriate and effective interventions.

< My Thoughts > “…accurately identify and begin…”

Accurately identifying and beginning treatment as early as possible is the resounding mantra, in the world of autism. The problem is finding those qualified clinicians who have zeroed in on the best testing; then, having found interventions which have zeroed in on matching the child’s needs with the best treatments.

Or, finding qualified professionals using the ‘best practices’ and/or ‘evidence-based’ practices. This is a challenge within itself. Added to that, everything is extremely costly and if it is a relatively new field or procedure, insurance companies may not want to help families finance it. Getting an accurate diagnosis, though, is the critical first step towards finding your child’s future independence and wellbeing.

Note: More about Insurance and Resources in UNIT 6.

Farmer & Reupert (2013) quote a parent as saying, “I feel as if I now understand what it’s like in my son’s world. I now know what Autism is.” When parents have an explanation of their child’s behavior and possible thinking, they are better able to accept that picture of their child. It’s very important for parents to accept the possibilities and expectations for their children, because treatment and intervention depends greatly on parent reports and observation.

< My Thoughts > “…that picture of their child.”

Parents may become convinced that special treatments and/or interventions will ‘cure’ the autism. But, to date there are NO cures, and there are NO specific ‘autism’ blood tests. Real 'data' may be found from assessments, much of which relies on ‘parent reporting’ information on questionnaires; parent responses which are open to interpretation by a technician.

To complicate things, the child’s developmental trajectory may take a zig-zagging course over time. Severe symptoms may even seem to abate or disappear periodically. This becomes especially difficult in separating these changes from the results of any therapies the child is engaged in. Sometimes therapy results overlap. And, sometimes it seems as if the ‘picture’ is just never really clear or complete. But, getting an accurate diagnosis is the critical first step towards finding your child’s future independence and wellbeing.

REFERENCES: UNIT 2; CHAPTER 1 ~ INTRODUCTION

Becerra-Culqui, T, Lynch, F., et al. (2018). Parental First Concerns & Timing of Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis; Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders; V48, p3367-3376.

Cademy, L. (2013). The Aspie Parent: the First Two Years, A Collection of Posts from the Aspie Parent Blog; eBook Edition.

Cettina, T. (2017). Special Needs Children: Should I Label My Kid?; Retrieved online from: http://www.parenting.com/article/special-needs-children on 6/26/17/

Farmer, J., & Reupert, A. (2013). Understanding Autism & Understanding My Child with Autism; Australian Journal of Rural Health; V21:1, p20-17.

Hart, A. (2011). Brains, Trains & Video Games: Living the Autism Life; eBook Edition.

Merchent, T. (2007). He’s Not Autistic, But: How We Pulled Our Son from the Mouth of the Abyss; eBook Edition.

Park, A. (2015). Researchers Zero In On The Best Way To Diagnose Autism; TIME USE, LLC; Retrieved online from – https://time.com/4017909/diagnosing-autism/

UNIT 2 – Why Is It Autism? – CHAPTER 1 – DIAGNOSIS & DSM-5

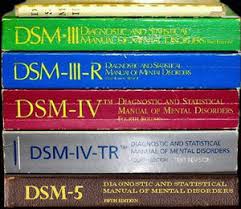

DIAGNOSIS & DSM-5

Autism Symptom Disorder (ASD) is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition (DSM-5). The DSM-5, published in 2013 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) is considered to be the principal authority used in the United States to specify the classification and classification codes of mental disorders.

Myers, et al. (2018) inform us that increases in the numbers of new ASD case identification is used in geographical areas, as needed for identifying and planning of educational, social, and medical services which are expected to be needed. They also evaluate trends over time, according to total special education and developmental services conducted.

< My Thoughts > “…used in the United States to specify…”, “…educational, social, and medical services…”

In the United States, data from geographical areas is used to evaluate trends over time. Thus, identifying and planning for future educational, social, and medical services. Hopefully, if the data shows an increase in autism diagnoses, then new community healthcare providers and educational settings will be provided, allowing more services for those individuals with autism.

Such data may also influence that when a child is from a ‘marginalized’ area, they will likely be considered ‘disadvantaged’, and the reason for their developmental delay. This may or may not be factual, but it should be helpful if parents are aware of this possible mindset when receiving or questioning a diagnosis.

Retrieved online from Elsevier (2021), is a study which first appeared in Biological Psychiatry, by its authors Whittle, S. and Rakesh, D. Studying the brain scans of over 7,000 children, ages 9 -10, found clear differences in brain regions. Magnetic Resonance Imagining (MRI) brain scans, identified the amount of or lack of ‘functional activity’, connecting one region of the brain to the other.

These identified brain differences were in children who were considered to be from disadvantaged areas. Neighborhoods with multiple risk factors, such as pollution, crime, and lower-quality schools and healthcare.

< My Thoughts > “…disadvantaged areas.”

Also, these geographical areas lack both community gardens and after-school enrichment programs. There also seems to be little or no access to healthcare. And, no public transportation connecting more advantaged neighborhoods with necessary services, or grocery stores, well supplied with fresh produce.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria – Retrieved online from – Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee; United States Department of Health & Human Services; aka IACC; include specifying in the diagnostic criteria –

Developmental milestones, for the above, and also including developmental ‘regression’ is considered important to diagnose, during or beyond the 18-month well-baby visit.

< My Thoughts > “…including developmental ‘regression’…”

When considering developmental ‘regression’, beyond 18-months, the idea of whether its autism ‘onset’, sudden ‘regression’, or whether ‘signs’ of autism have always been there is the conundrum. You may never really know, but what is important is meeting the child’s immediate needs. Get them the help they are asking for; in the only way they know how.

Note: Valuable LINKs to IACC | Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee – https://iacc.hhs.gov and https://iacc.hhs.gov/about-iacc/subcommittees/resources/dsm5-diagnostic-cr iteria.shtml/

DIAGNOSIS & DSM-5

Autism Symptom Disorder (ASD) is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition (DSM-5). The DSM-5, published in 2013 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) is considered to be the principal authority used in the United States to specify the classification and classification codes of mental disorders.

Myers, et al. (2018) inform us that increases in the numbers of new ASD case identification is used in geographical areas, as needed for identifying and planning of educational, social, and medical services which are expected to be needed. They also evaluate trends over time, according to total special education and developmental services conducted.

< My Thoughts > “…used in the United States to specify…”, “…educational, social, and medical services…”

In the United States, data from geographical areas is used to evaluate trends over time. Thus, identifying and planning for future educational, social, and medical services. Hopefully, if the data shows an increase in autism diagnoses, then new community healthcare providers and educational settings will be provided, allowing more services for those individuals with autism.

Such data may also influence that when a child is from a ‘marginalized’ area, they will likely be considered ‘disadvantaged’, and the reason for their developmental delay. This may or may not be factual, but it should be helpful if parents are aware of this possible mindset when receiving or questioning a diagnosis.

Retrieved online from Elsevier (2021), is a study which first appeared in Biological Psychiatry, by its authors Whittle, S. and Rakesh, D. Studying the brain scans of over 7,000 children, ages 9 -10, found clear differences in brain regions. Magnetic Resonance Imagining (MRI) brain scans, identified the amount of or lack of ‘functional activity’, connecting one region of the brain to the other.

These identified brain differences were in children who were considered to be from disadvantaged areas. Neighborhoods with multiple risk factors, such as pollution, crime, and lower-quality schools and healthcare.

< My Thoughts > “…disadvantaged areas.”

Also, these geographical areas lack both community gardens and after-school enrichment programs. There also seems to be little or no access to healthcare. And, no public transportation connecting more advantaged neighborhoods with necessary services, or grocery stores, well supplied with fresh produce.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria – Retrieved online from – Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee; United States Department of Health & Human Services; aka IACC; include specifying in the diagnostic criteria –

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder

- Severity Levels for Autism Spectrum Disorder

Developmental milestones, for the above, and also including developmental ‘regression’ is considered important to diagnose, during or beyond the 18-month well-baby visit.

< My Thoughts > “…including developmental ‘regression’…”

When considering developmental ‘regression’, beyond 18-months, the idea of whether its autism ‘onset’, sudden ‘regression’, or whether ‘signs’ of autism have always been there is the conundrum. You may never really know, but what is important is meeting the child’s immediate needs. Get them the help they are asking for; in the only way they know how.

Note: Valuable LINKs to IACC | Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee – https://iacc.hhs.gov and https://iacc.hhs.gov/about-iacc/subcommittees/resources/dsm5-diagnostic-cr iteria.shtml/

Ming, et al. (2011) advise that ASD is most often diagnosed between the ages of 2-3 years old; saying that the older child may NOT respond to obvious social cues, body language, or facial expressions. S/he may NOT smile when happy, or laugh at a joke. The child may speak in a flat, robotic kind of way.

Other subtle indicators of concern may be that the child dislikes change, or wants to eat the same food, repeatedly; or that they are having trouble in school. There are other neurological disorders that can affect children, like Rett syndrome, or other ‘genetic’ disorders, but they are rare. Present at birth, Rett syndrome is a neurological genetic disorder that causes severe muscle movement disability.

Note: More about Rett Syndrome in Unit 2, Chapter 2.

Dobbs (2017) decides that ‘regression’ could be described as ‘streetlights and tiny things’ – One challenge in spotting autism’s onset is what scientists call the ‘streetlight effect’. The human tendency to look for things where we can most easily see them (whatever’s visible beneath the proverbial lamppost) even though what we seek may lie elsewhere; off in the shadows, or even in the dark.

He shares that Sally Ozonoff (2015) has long held to be true that regression is a ‘subtype’ of autism. Studying autism, she recalls that accepting ‘regression’ meant accepting the ‘great divide’; believing that children abruptly lose their learned skills. But, in the decades since, she believes that those once clear ‘regression’ boundaries have seemed to have faded.

< My Thoughts > “…clear ‘regression’ boundaries…”

Those once clear ‘regression’ boundaries may seemed to have faded. Especially when considering making a diagnosis of ‘regression’, the traditional boundary becomes even more ambiguous. Was the child always somewhere on the autism spectrum, but the differences just weren’t that visible? Or, is this a ‘late onset’ occurrence which now looks like ‘more’ than a developmental delay, but is a definite loss of skills – ‘regression’.

Hayes (2020) says that historically when a diagnosis is made, it is like ‘drawing a line in the sand’. While, the world of ‘autism’ takes place outside the traditional medical field, clinicians must find that space between the fields where ‘autism’ boundaries lie.

Often, the line between the ‘lay’ person’s and the ‘medical’ person’s real expertise is blurred. The reason they feel, is that the parents expect the clinicians will ‘know’ everything about autism; and the medical persons rely on the parents to share everything they ‘know’ about their child’s autism. Thus, the expectation is that a carefully defined line will be drawn and a clear ‘autism’ diagnosis will be made.

< My Thoughts > “…‘like drawing a line in the sand’…”

Yale Child Study Center researcher, K. Chawarska claims that when discerning autism from an innate developmental problem, or a problem of regression, it is like trying to ‘draw a line in shifting sand’. For instance, before ‘losing a skill’ can be considered to be ‘regression’, some believe that a child must have been proficient in that skill for at least 3 months, prior to losing it. Video diaries of the child may aid in determining onset.

Piven (2015) – My take on ‘regression’ is that it’s a misnomer, that autism has always been there. Believing that you would have seen those ‘signs’ of autism early on, if you knew what to look for.

Brodie (2013) began suspecting regression when his son Scott stopped making eye contact and no longer responded to his name. At 25-months-old, he lost his ability to engage in imaginative play and lost the few words he once used. Now, Scott would spin himself or objects. Started wiggling his fingers in front of his eyes, watched the same one or two videos, forwarding and rewinding them over and over.

While Brignell, et al. (2015) explain autism’s different trajectories, such as –

Some say that all children go through both delays and learning spurts. They call it the natural ‘over-pruning’ a child’s brain does to make room for new growth. Others think of autism emerging as a dynamic multifaceted version of brain development.

Thomas, M. & Davis (2016) present a new hypothesis of the underlying cause of autistic spectrum disorders (ASD). This ‘over-pruning’ perspective explains the lack of exact timing in the manifestation of the disorder. Proposing that autism is a result of the ‘over-pruning’ of brain connectivity early in a child’s development. An overly-aggressive synaptic pruning as an ‘exaggerated phase’ of brain development, in infancy and early childhood. Thus, explaining how unaffected or mildly at-risk siblings may differ in their inheritance of autism genes.

Johnson (2014) says that discovering your child has autism may come in the most subtle ways. It’s in the little things. When your two-year-old doesn’t look at you as you enter a room. When your three-year-old still isn’t speaking in intelligible, complete sentences. When everyone else’s children are playing together, and your daughter is under a tree, digging for who knows what. When a frustrated teenage swimming instructor says, “Lady, I think there’s something wrong with your kid.” That’s when you start to realize.

When Sophie was a baby and even a toddler, we would enter a restaurant and she would talk to everyone. I used to say she never met a stranger. She was the social butterfly I supposed that my child would be, at 12 months. Exactly what I thought she would be.

And then something changed.

It was a gradual realization, too, as it often is.

At first, I made excuses, as I think most parents do.

Sophie chooses to ignore me because she is a little diva. She doesn’t want to play with the other kids because she is too sophisticated for them. She doesn’t speak in complete sentences because I always know what she wants, and I let her get away with pointing. She’s just a little different and that’s okay. If the pediatrician wasn’t losing any sleep over it, I wasn’t going to either.

Then, Sophie started pre-school. The differences in Sophie were apparent immediately to the staff, particularly the director. But, some of the things they said Sophie “couldn’t” or “wouldn’t” do at school, she was doing at home.

The teachers were very concerned and my concern was growing by the minute. And yet, still, I waited. I was pregnant with Ariel, Sophie’s little sister. I was working a lot. These are the excuses I used.

Much as you want to know what is going on with your baby, you also don’t want to know. And, if you don’t know if something is true or not, you can always hope that it isn’t. Finally, when Sophie was two-and-a-half, we decided to have her evaluated.

< My Thoughts > “…you can always hope that it isn’t.

But if it is autism, then it’s time to choose a direction.

Ambersley (2013) – Our family has chosen the path of ‘autism light’, which enables and engages our son Aaron so that he can set goals, live his dreams, and exceed expectations at his pace and on his terms.

The psychologist who evaluated my son shared with me that with a lot of patients, he can immediately tell that, ‘the lights are out and nobody’s home’. That very profound statement that had me thinking, if the lights are out, what does it take to turn the lights on?

Autism is very unpredictable when looking ahead into the future. It is rather difficult to determine which of those autistic challenges and tendencies will stick with him for a lifetime and which, with help, will gradually disappear. Real change is possible and inevitable when corrective action is taken. I knew that finding a pediatrician was very important to building a history with treating Aaron. That allowed our son to have a great foundation to build on. The best gift we could ever provide to our son was ‘early intervention’.

< My Thoughts > “…corrective action is taken.”

Often, finding a Developmental Pediatrician means first taking your child to the general practitioner that is on your insurance provider list. Next, convince that practitioner to refer you to a developmental specialist. Following the correct protocol is very important, unless you have a house to mortgage. And, be certain to take evidence with you. A simple video made on your phone, of your child acting in ways that don’t seem to have any explainable function; such as hurting themselves, or less dangerous, but ‘unpurposeful’ behavior. When the doctor finally sees the things which concern you, it can lead to an accurate diagnosis.

According to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), there should be concern, if by 18 months the child –

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that children be screened for autism between 18 and 24 months, or whenever a parent or provider is concerned. Retrieved online from – https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/milestones-18mo.html/

The AAP also recommends ongoing surveillance after an initial ASD-specific screening. Autism screening tools, such as the M-CHAT, are considered more accurate when used in conjunction with clinical judgment. Children with autism from minority backgrounds are often diagnosed at a later age than other children. The concepts of screening, early identification and early intervention may be unfamiliar for families from marginalized cultural backgrounds. For many families, these concepts are culturally bound, leading to the perception that if their children participate they will be stigmatized in their communities.

Effectively serving school-age students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) requires a professional who possesses specialized knowledge, skills, and understanding. When students with ASD are from culturally or linguistically diverse (CLD) families, the professionals assessing and providing services to the students need the additional dimension of how their cultural and linguistic differences may affect identification, assessment, and treatment strategies. Retrieved online from – National University Graduate Program Lecture Notes: Developmental Screening Assignment for Unit 4.2 (end of Lecture 4.2; 2013).

Other subtle indicators of concern may be that the child dislikes change, or wants to eat the same food, repeatedly; or that they are having trouble in school. There are other neurological disorders that can affect children, like Rett syndrome, or other ‘genetic’ disorders, but they are rare. Present at birth, Rett syndrome is a neurological genetic disorder that causes severe muscle movement disability.

Note: More about Rett Syndrome in Unit 2, Chapter 2.

Dobbs (2017) decides that ‘regression’ could be described as ‘streetlights and tiny things’ – One challenge in spotting autism’s onset is what scientists call the ‘streetlight effect’. The human tendency to look for things where we can most easily see them (whatever’s visible beneath the proverbial lamppost) even though what we seek may lie elsewhere; off in the shadows, or even in the dark.

He shares that Sally Ozonoff (2015) has long held to be true that regression is a ‘subtype’ of autism. Studying autism, she recalls that accepting ‘regression’ meant accepting the ‘great divide’; believing that children abruptly lose their learned skills. But, in the decades since, she believes that those once clear ‘regression’ boundaries have seemed to have faded.

< My Thoughts > “…clear ‘regression’ boundaries…”

Those once clear ‘regression’ boundaries may seemed to have faded. Especially when considering making a diagnosis of ‘regression’, the traditional boundary becomes even more ambiguous. Was the child always somewhere on the autism spectrum, but the differences just weren’t that visible? Or, is this a ‘late onset’ occurrence which now looks like ‘more’ than a developmental delay, but is a definite loss of skills – ‘regression’.

Hayes (2020) says that historically when a diagnosis is made, it is like ‘drawing a line in the sand’. While, the world of ‘autism’ takes place outside the traditional medical field, clinicians must find that space between the fields where ‘autism’ boundaries lie.

Often, the line between the ‘lay’ person’s and the ‘medical’ person’s real expertise is blurred. The reason they feel, is that the parents expect the clinicians will ‘know’ everything about autism; and the medical persons rely on the parents to share everything they ‘know’ about their child’s autism. Thus, the expectation is that a carefully defined line will be drawn and a clear ‘autism’ diagnosis will be made.

< My Thoughts > “…‘like drawing a line in the sand’…”

Yale Child Study Center researcher, K. Chawarska claims that when discerning autism from an innate developmental problem, or a problem of regression, it is like trying to ‘draw a line in shifting sand’. For instance, before ‘losing a skill’ can be considered to be ‘regression’, some believe that a child must have been proficient in that skill for at least 3 months, prior to losing it. Video diaries of the child may aid in determining onset.

Piven (2015) – My take on ‘regression’ is that it’s a misnomer, that autism has always been there. Believing that you would have seen those ‘signs’ of autism early on, if you knew what to look for.

Brodie (2013) began suspecting regression when his son Scott stopped making eye contact and no longer responded to his name. At 25-months-old, he lost his ability to engage in imaginative play and lost the few words he once used. Now, Scott would spin himself or objects. Started wiggling his fingers in front of his eyes, watched the same one or two videos, forwarding and rewinding them over and over.

While Brignell, et al. (2015) explain autism’s different trajectories, such as –

- Early developmental delays with no loss of skills.

- Early delays, plus loss of skills.

- No early delays and no skill loss, but ‘plateauing’ showing no gains.

- ‘Regression’ with no delays before showing a clear loss of skills.

Some say that all children go through both delays and learning spurts. They call it the natural ‘over-pruning’ a child’s brain does to make room for new growth. Others think of autism emerging as a dynamic multifaceted version of brain development.

Thomas, M. & Davis (2016) present a new hypothesis of the underlying cause of autistic spectrum disorders (ASD). This ‘over-pruning’ perspective explains the lack of exact timing in the manifestation of the disorder. Proposing that autism is a result of the ‘over-pruning’ of brain connectivity early in a child’s development. An overly-aggressive synaptic pruning as an ‘exaggerated phase’ of brain development, in infancy and early childhood. Thus, explaining how unaffected or mildly at-risk siblings may differ in their inheritance of autism genes.

Johnson (2014) says that discovering your child has autism may come in the most subtle ways. It’s in the little things. When your two-year-old doesn’t look at you as you enter a room. When your three-year-old still isn’t speaking in intelligible, complete sentences. When everyone else’s children are playing together, and your daughter is under a tree, digging for who knows what. When a frustrated teenage swimming instructor says, “Lady, I think there’s something wrong with your kid.” That’s when you start to realize.

When Sophie was a baby and even a toddler, we would enter a restaurant and she would talk to everyone. I used to say she never met a stranger. She was the social butterfly I supposed that my child would be, at 12 months. Exactly what I thought she would be.

And then something changed.

It was a gradual realization, too, as it often is.

At first, I made excuses, as I think most parents do.

Sophie chooses to ignore me because she is a little diva. She doesn’t want to play with the other kids because she is too sophisticated for them. She doesn’t speak in complete sentences because I always know what she wants, and I let her get away with pointing. She’s just a little different and that’s okay. If the pediatrician wasn’t losing any sleep over it, I wasn’t going to either.

Then, Sophie started pre-school. The differences in Sophie were apparent immediately to the staff, particularly the director. But, some of the things they said Sophie “couldn’t” or “wouldn’t” do at school, she was doing at home.

The teachers were very concerned and my concern was growing by the minute. And yet, still, I waited. I was pregnant with Ariel, Sophie’s little sister. I was working a lot. These are the excuses I used.

Much as you want to know what is going on with your baby, you also don’t want to know. And, if you don’t know if something is true or not, you can always hope that it isn’t. Finally, when Sophie was two-and-a-half, we decided to have her evaluated.

< My Thoughts > “…you can always hope that it isn’t.

But if it is autism, then it’s time to choose a direction.

Ambersley (2013) – Our family has chosen the path of ‘autism light’, which enables and engages our son Aaron so that he can set goals, live his dreams, and exceed expectations at his pace and on his terms.

The psychologist who evaluated my son shared with me that with a lot of patients, he can immediately tell that, ‘the lights are out and nobody’s home’. That very profound statement that had me thinking, if the lights are out, what does it take to turn the lights on?

Autism is very unpredictable when looking ahead into the future. It is rather difficult to determine which of those autistic challenges and tendencies will stick with him for a lifetime and which, with help, will gradually disappear. Real change is possible and inevitable when corrective action is taken. I knew that finding a pediatrician was very important to building a history with treating Aaron. That allowed our son to have a great foundation to build on. The best gift we could ever provide to our son was ‘early intervention’.

< My Thoughts > “…corrective action is taken.”

Often, finding a Developmental Pediatrician means first taking your child to the general practitioner that is on your insurance provider list. Next, convince that practitioner to refer you to a developmental specialist. Following the correct protocol is very important, unless you have a house to mortgage. And, be certain to take evidence with you. A simple video made on your phone, of your child acting in ways that don’t seem to have any explainable function; such as hurting themselves, or less dangerous, but ‘unpurposeful’ behavior. When the doctor finally sees the things which concern you, it can lead to an accurate diagnosis.

According to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), there should be concern, if by 18 months the child –

- Doesn’t point or show things to others

- Doesn’t walk

- Doesn’t know what familiar things are for

- Doesn’t copy others

- Doesn’t gain new words

- Doesn’t have at least 6 words

- Doesn’t mind when caregiver leaves or returns

- Doesn’t use skills s/he once had

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that children be screened for autism between 18 and 24 months, or whenever a parent or provider is concerned. Retrieved online from – https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/milestones-18mo.html/

The AAP also recommends ongoing surveillance after an initial ASD-specific screening. Autism screening tools, such as the M-CHAT, are considered more accurate when used in conjunction with clinical judgment. Children with autism from minority backgrounds are often diagnosed at a later age than other children. The concepts of screening, early identification and early intervention may be unfamiliar for families from marginalized cultural backgrounds. For many families, these concepts are culturally bound, leading to the perception that if their children participate they will be stigmatized in their communities.

Effectively serving school-age students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) requires a professional who possesses specialized knowledge, skills, and understanding. When students with ASD are from culturally or linguistically diverse (CLD) families, the professionals assessing and providing services to the students need the additional dimension of how their cultural and linguistic differences may affect identification, assessment, and treatment strategies. Retrieved online from – National University Graduate Program Lecture Notes: Developmental Screening Assignment for Unit 4.2 (end of Lecture 4.2; 2013).

Wong & Heriot (2007) know that parents with whom they have encountered, when receiving an autism diagnosis, mostly maintain a hopeful outlook for their child’s future. This attitude enables them to more easily pursue treatment options, and to cope with the day-to-day challenges and the stress involved. Mothers especially, they say, hold a sense of reaching the child and accepting the diagnosis, at the same time. This study showed that even if parents’ optimism was unrealistic, they continued to hold an overall ‘hopeful’ view of the future for their child.

< My Thoughts > “…sense of reaching the child.”

Many, many fathers as well as mothers hold that same sense of commitment. The ‘sense of reaching their child’ no matter what it takes. Fathers have lost their jobs due to time-off. Some have changed their careers to obtain better family insurance. Still holding a sense of future ‘good’ news, in the face of receiving an autism diagnosis, Parents have made untold sacrifices for their child with autism.

Whiffen (2009) – “So Mrs. Whiffen,” she pauses and smiles, “I am happy to tell you that Clay does NOT currently meet the DSM-V diagnostic criteria for a diagnosis on the autism spectrum. He is well below the cutoff for autism on the ADI-R and ADOS tests.”

Dr. Gale begins, “Clay is a charming boy and I believe the test results accurately reflect his current levels of neurocognitive and neurobehavioral functioning.” She takes out her notebook, “On the neurocognitive analysis,” she continues, “his subscale scores and core domain score consistently ranged from average to above average.” I feel a rush of excitement.

“He does,” she continues, “demonstrate patterns of relative weakness across areas of social interaction, pragmatic language, interests, and behavior. However, none of Clay’s observed qualitative differences are significant enough to meet the criteria for a diagnosis of autism. It is my professional opinion that Clay could be considered a candidate for placement in a mainstream kindergarten classroom.”

We make the twisty canyon drive home with the windows down and the radio up. “We’re free!” I shout above the roar of the wind. “We’re free!”

“Clay, we kept fighting, buddy. We never gave up. We did it!”

< My Thoughts > “We did it!”

Even children without developmental issues go through periods of plateauing, when they seem to take a break from growing and/or learning. Or, they unexpectedly begin accelerating in growth and learning. When this does happen, one would hope that both the parents and the educators would still keep a careful eye on that child’s patterns of strengths and relative weaknesses. And, that there will be routine and careful ‘follow-ups’ to all ‘interventions’ and developmental changes.

Note: More about previously mentioned ASD assessments, such as – M-Chat, ADI-R, & ADOS in Units 1 & 4.

Piven (2015) fears that several things may interfere with a child’s clear and accurate autism diagnosis. For instance, relying on the misinterpretation or subjectivity of parent reporting, and the possible misinterpretation of data results.

Healthline Staff Writer (2020) clarifies that a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-4) diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not-Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) was given in the past if a person was determined to have some autism symptoms. But they did NOT meet the full diagnostic criteria for conditions such as autistic disorder and/or Asperger’s syndrome.

< My Thoughts > “…did NOT meet the full diagnostic criteria…”

When a child, adolescent, or adult received a diagnosis based on the 1994 American Psychiatric Association (APA), DSM - 4th Edition, they may have to ‘requalify’ for a new diagnosis under the latest 2013 DSM - 5th Edition. This could affect many things, such as educational services and insurance eligibility qualifications.

Thrive Works Staff Writer (2019) states that the purpose of the DSM-5 revision of the DSM-4 was said to improve diagnostic efficacy, accuracy, and consistency when diagnosing mental disorders. A general overview of the diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), per the DSM-5 is – Persistent (i.e., regular) deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts (criterion A).

This can include developmental problems with:

• Social-emotional reciprocity (e.g., back and forth conversation).

• Nonverbal communicative behaviors (e.g., abnormalities in eye contact and body language).

• Developing, maintaining, and understanding social (age-appropriate) relationships.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) criteria for diagnosis also requires that the person show –

• Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities such as stereotyped or repetitive motor movements.

• Ritualized patterns or inflexible adherence to routines.

• Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in their intensity or focus.

• And/or hyper/hypo reactivity to sensory input (Criterion B).

Other ASD criteria also include these symptoms –

• Must be present in the individual’s early developmental period.

• Must cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.

• Are NOT better explained by intellectual disability (e.g., intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay (Criterion C through E).

‘Severity specifiers’ are given for social communication impairments (Criterion A) and restricted repetitive patterns of behavior (Criterion B). Severity for both Criterion A and B are listed at three different levels:

• Level 1 – requiring support

• Level 2 – requiring substantial support

• Level 3 – requiring very substantial support

Note: The revision DSM-5 replaced the previous edition, the DSM-4 which now has the ‘severity level’ indicated, as well as for which impairment (e.g., social communication and/or repetitive patterns of behavior). For example, a ‘severity level’ of needs ‘intense’ support for deficits in social communication, but only designated as needing ‘moderate’ support for restrictive repetitive behaviors.

< My Thoughts > “…revision DSM-5 replaced the previous edition, the DSM-4.”

This DSM-5 diagnostic ‘criteria’ replacement was accepted as a clarification of the previous version, DSM-4. This new interpretation created classification changes, and in some cases, resulted in disqualification of prior eligibilities. One of the reasons given was that conditions previously thought of as needing short-term intervention, medication and therapies, now reclassified, necessitating a more in-depth diagnostic look.

This can be very helpful when deciding upon the appropriate ‘intervention’, without overdoing ‘support’ in areas where it may be layered into a more or less substantial support.

< My Thoughts > “…sense of reaching the child.”

Many, many fathers as well as mothers hold that same sense of commitment. The ‘sense of reaching their child’ no matter what it takes. Fathers have lost their jobs due to time-off. Some have changed their careers to obtain better family insurance. Still holding a sense of future ‘good’ news, in the face of receiving an autism diagnosis, Parents have made untold sacrifices for their child with autism.

Whiffen (2009) – “So Mrs. Whiffen,” she pauses and smiles, “I am happy to tell you that Clay does NOT currently meet the DSM-V diagnostic criteria for a diagnosis on the autism spectrum. He is well below the cutoff for autism on the ADI-R and ADOS tests.”

Dr. Gale begins, “Clay is a charming boy and I believe the test results accurately reflect his current levels of neurocognitive and neurobehavioral functioning.” She takes out her notebook, “On the neurocognitive analysis,” she continues, “his subscale scores and core domain score consistently ranged from average to above average.” I feel a rush of excitement.

“He does,” she continues, “demonstrate patterns of relative weakness across areas of social interaction, pragmatic language, interests, and behavior. However, none of Clay’s observed qualitative differences are significant enough to meet the criteria for a diagnosis of autism. It is my professional opinion that Clay could be considered a candidate for placement in a mainstream kindergarten classroom.”

We make the twisty canyon drive home with the windows down and the radio up. “We’re free!” I shout above the roar of the wind. “We’re free!”

“Clay, we kept fighting, buddy. We never gave up. We did it!”

< My Thoughts > “We did it!”

Even children without developmental issues go through periods of plateauing, when they seem to take a break from growing and/or learning. Or, they unexpectedly begin accelerating in growth and learning. When this does happen, one would hope that both the parents and the educators would still keep a careful eye on that child’s patterns of strengths and relative weaknesses. And, that there will be routine and careful ‘follow-ups’ to all ‘interventions’ and developmental changes.

Note: More about previously mentioned ASD assessments, such as – M-Chat, ADI-R, & ADOS in Units 1 & 4.

Piven (2015) fears that several things may interfere with a child’s clear and accurate autism diagnosis. For instance, relying on the misinterpretation or subjectivity of parent reporting, and the possible misinterpretation of data results.

Healthline Staff Writer (2020) clarifies that a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-4) diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not-Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) was given in the past if a person was determined to have some autism symptoms. But they did NOT meet the full diagnostic criteria for conditions such as autistic disorder and/or Asperger’s syndrome.

< My Thoughts > “…did NOT meet the full diagnostic criteria…”

When a child, adolescent, or adult received a diagnosis based on the 1994 American Psychiatric Association (APA), DSM - 4th Edition, they may have to ‘requalify’ for a new diagnosis under the latest 2013 DSM - 5th Edition. This could affect many things, such as educational services and insurance eligibility qualifications.

Thrive Works Staff Writer (2019) states that the purpose of the DSM-5 revision of the DSM-4 was said to improve diagnostic efficacy, accuracy, and consistency when diagnosing mental disorders. A general overview of the diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), per the DSM-5 is – Persistent (i.e., regular) deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts (criterion A).

This can include developmental problems with:

• Social-emotional reciprocity (e.g., back and forth conversation).

• Nonverbal communicative behaviors (e.g., abnormalities in eye contact and body language).

• Developing, maintaining, and understanding social (age-appropriate) relationships.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) criteria for diagnosis also requires that the person show –

• Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities such as stereotyped or repetitive motor movements.

• Ritualized patterns or inflexible adherence to routines.

• Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in their intensity or focus.

• And/or hyper/hypo reactivity to sensory input (Criterion B).

Other ASD criteria also include these symptoms –

• Must be present in the individual’s early developmental period.

• Must cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.

• Are NOT better explained by intellectual disability (e.g., intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay (Criterion C through E).

‘Severity specifiers’ are given for social communication impairments (Criterion A) and restricted repetitive patterns of behavior (Criterion B). Severity for both Criterion A and B are listed at three different levels:

• Level 1 – requiring support

• Level 2 – requiring substantial support

• Level 3 – requiring very substantial support

Note: The revision DSM-5 replaced the previous edition, the DSM-4 which now has the ‘severity level’ indicated, as well as for which impairment (e.g., social communication and/or repetitive patterns of behavior). For example, a ‘severity level’ of needs ‘intense’ support for deficits in social communication, but only designated as needing ‘moderate’ support for restrictive repetitive behaviors.

< My Thoughts > “…revision DSM-5 replaced the previous edition, the DSM-4.”

This DSM-5 diagnostic ‘criteria’ replacement was accepted as a clarification of the previous version, DSM-4. This new interpretation created classification changes, and in some cases, resulted in disqualification of prior eligibilities. One of the reasons given was that conditions previously thought of as needing short-term intervention, medication and therapies, now reclassified, necessitating a more in-depth diagnostic look.

This can be very helpful when deciding upon the appropriate ‘intervention’, without overdoing ‘support’ in areas where it may be layered into a more or less substantial support.

(This child seems to be engaging in ’typically purposeless’ autistic behavior. Often,, they will also be prone on the floor, repeatedly spinning a toy.

Fedele (2018) feels that people who are prone to ‘restrictive repetitive’ behaviors (RRBs) have learned to cope through a wide range of behaviors; such as obsessions, ritual and insistence on sameness, and layers of other persistent manifestations.

In nursing, when I first began working with people with autism, people across the spectrum, I learned to recognize cues that they were having some sort of difficulty. They would retreat into Restrictive Repetitive Behaviors (RRBs), experiencing anxiety without the necessary therapeutic tools or training to solve the problem any other way.

Also, I learned to induce them to learn new tasks by first playing my ukulele. And, by taking a large chunk of the task, and breaking it into smaller pieces of the whole. Registered Nurses can take up the nursing challenge by learning to understand and work with the autism population. Saying that this sometimes takes years.

Barnes (2014) tells us – My name is Elizabeth and I am an Autism Mom. Our son, who we will call the Navigator, is nine and was diagnosed on the Autism Spectrum at the age of seven. Before his diagnosis, I had heard of Autism – non-verbal children who don’t like to be touched, who rocked, and who ritually lined things up. My son had none of these characteristics, so when he started having difficulties in pre-school interacting with other children, transitioning from one play area to the next, following instructions from teachers and staff, I didn’t initially think “neurological disorder.”

Then came a call from his first-grade teacher: “I am not a doctor or psychologist, but I spent 15 years in Special Education, and I think your son may have Asperger’s.” One of the American Psychiatric Association descriptions is that, “symptoms are not fully recognized until social demands exceed the child’s capacity.”

After testing by both the school and privately, he was diagnosed to be high-functioning on the Autism spectrum; Asperger’s. He receives special education services through the school.

Within a year after the diagnosis, I quit my full-time job to stay home and provide him structure and support. It was a relief to no longer feel like his behavioral issues were the result of bad parenting, or something we were doing wrong.

There is no one thing, or even series of things that work all the time, or are even discernible as a pattern. There is a need for constant analysis and creativity, which is exhausting and sometimes seemingly fruitless. Now when he melts down or perseverates I can (most of the time) calmly help him through it and not cry afterwards (most of the time).

< My Thoughts > “…need for constant analysis and creativity…”

This Barnes excerpt says so much. It tells us so candidly how Elizabeth felt that she needed to change her identity from ‘everyday’ mom to ‘Autism’ mom.

Bent, et al. (2016) believe that access to specific autism intervention and funding services are largely dependent on an exact diagnosis of ASD. Changes to the DSM-5 diagnosis criteria may therefore have a substantial impact on access to, or continuation of services. They noted that data had been ‘de-identified’ (personal information identifying ‘study participants’, between 2010 and 2015, has been electronically removed) for the 32,100 children aged under 7 years utilized in this study.

Suggesting that the more stringent DSM-5 criteria may be responsible for the seemingly ‘downtrend’ in recent diagnoses. Another reason may be the recent inclusion of – sensory interests, sensitivity, aversions, and removal of language difficulties from the core DSM-5 criteria. In all regards, the authors remind us that program eligibility criteria require the diagnose to be confirmed, exactly. The DSM-5 criteria must be designated by a pediatrician, psychiatrist, or qualified multidisciplinary team which includes a psychologist and speech pathologist. They suggest that more cases may be identified as clinicians become familiar with the new protocol, thus resulting in longer waiting time for anxious parents.

< My Thoughts > “…more cases may be identified…”

As more cases are identified, there is a need for constant analysis, creativity, and patience as a parent of a child with autism. Also, as an experienced special education teacher with a heavily increasing caseload of students with autism, this is so true. Added to that – There is no one solution or even series of solutions, or educational programs which will work every time for every child. Parents working with teachers as well as the multidisciplinary team will succeed.

Kim, et al. (2018) disclose that fundamental questions regarding the classification of the disorder remain unresolved. Added to that are the meaningful differences between parent and teacher reports regarding the child’s behavior. The need for collecting more in-depth data.

They site Initial Parent and Teacher Reports which begin by using vague descriptive words or phrases, such as –

Acting peculiar …

Doesn’t do well…

Not interested…

Unaware of…

Inappropriate response to…

Acts or reacts strangely…

Upsets easily…

Strange fascination for…

Excessive preoccupation with…

< My Thoughts > “…more in-depth data.”

In the new DSM-5, more ‘in-depth’ impairment criteria for autism classifies symptoms by also including such things as –

Thus, a clarified diagnosis could include one impairment needing Level 1 support, where a more severe impairment would require a Level 2, or Level 3 support.

Thomas, R., et al. (2016) think that most developmental problems are readily evident at the 18-month ‘well-baby’ visit. But these authors say that family physicians or pediatricians do NOT always know if the problem they’re seeing is due to the child’s environment, possibly inadequate parenting skills, or clinical screening problems.

< My Thoughts > “…developmental problems…”

Hopefully, developmental problems being seen by clinicians should be referred to a developmental specialist. Alarmingly, I have discovered that many generations of children have never experienced a scheduled ‘Well-Child’ visit by a pediatrician, but only are taken to see a doctor if they are sick. Sometimes this is due to the ‘insurance’ coverage, or lack thereof. Or, a multitude of resource, cultural, philosophical, and misinformation reasons.

According to the CDC, scheduling Well-Child visits with the child’s pediatrician at 18 months and 24 months should be considered essential. These visits determine how s/he is meeting developmental milestones. The following questions may be asked –

Parent and/or caregiver responses are very important in any child’s screening. If there are concerns, your doctor should be referring you to a developmental specialist. Without the primary doctor’s referral, insurance companies most certainly will refuse to pay for a specialist’s services.

Thrum, et al. (2007) a child is considered ‘non-verbal’ when they have passed the eighteen-month mark and have no language. Most children at this age would have “5 or more words used spontaneously on a daily basis.” There are also other given predictors of receptive language, such as a child responding to simple commands.

< My Thoughts > “…predictors…”

As a classroom teacher, before spending time teaching/learning new skills, one must determine if the child will be successful at learning this skill. Within a predictable measure, you may be able to determine if the child has ‘receptive language’. Will the child have the cognitive ability which allows them to process what is being said, to devote the sustained effort to focus, concentrate, and/or develop new skills?

An example of this would be if the child responds to simple commands such as, “Sit down”, “Stand up”, “Come here”. One must be careful here NOT to assume that if the child doesn’t respond to “Please stop,” that it’s because they don’t know what you are saying or don’t have receptive language. As it happens, the autistic child is NOT likely to ‘stop’ stimming, or eating dirt, or participating in other sensory needs when asked to. Sometimes ‘signing’ ‘stop’ will help.

Conti-Ramsden, et al. (2012) contribute that when a general pattern of stable language growth is not maintained; along with the child being nonverbal, that is a ‘predictor’. Also, when there seems to be ‘poor’ engagement in the world, that should be considered.

If the only thing stable is that the child has NOT shown gains in the area of verbal or nonverbal skills, then it becomes urgent to investigate further. They suggest looking at levels of performance across all developmental domains, as compared with typically developing children, in the same age group.

With the clarification that nonverbal skills are the ability to have both ‘expressive’ and ‘receptive’ language. Nonverbal communication includes the use of appropriate body language, facial expressions, eye contact, and general friendly responsiveness. Also, it is important to understand that if the child starts out with delayed language, but begins to develop skills on a more normal trajectory, then there may need to be the consideration or investigation of possible ‘plateauing’ and/or declining of developing skills.

< My Thoughts > “…’plateauing’ and/or declining of developing skills…”

For instance, when a child is working hard to develop new motor skills, such as walking, or becoming toilet trained, they may seem to become less aware of their communication skills. As previously mentioned, determining ‘exactly’ what is going on during a child’s developmental period, may be difficult.

When Sonny is trying to learn something new, he acts as if he doesn’t understand what you are saying to him. His ‘receptive language’ seems to be missing. But, of course it’s quite good. And, we know by now that his first reaction to ‘change’ is often a ‘negative’ one.

Then, when he wants something, instead of using ‘expressive language’, signing or using his device he tantrums or drags us to what he wants. We may say softly, “Use your words.” Or, we just play along, cueing him to his new skill as much as he will tolerate, then while he seems to be processing everything, we wait it out until he is ready. Once he learns his new skill, to the best of his ability, then its business as usual. Usually.

Cademy (2013) shares her collection of terms which she calls Alphabet Soup –

Aspie and AS – are both short for Asperger’s Syndrome, condition where the brain is wired differently than normal. In severe cases, this rewiring can cause autism, but most Aspies are able to be productive members of our modern world, if seen as a bit quirky…

NLD – stands for Non-verbal Learning Disorder. The main distinction is that people with NLD have problems decoding any and all non-verbal information, while Aspies can have excellent visual learning patterns.

PDD/NOS – is short for Pervasive Development Disorder. NOS – Not Otherwise Specified. In plain English, this means a person doesn’t have NLD, or Asperger’s, but definitely has something like them.

On the spectrum – a blanket term for anyone who has any autism spectrum condition, mild or severe or anything in between.

NT – neurotypical, the term used for people who are not on the spectrum.

Gifted, GT – lots of people with Asperger’s are smarter than average, either in a few areas or overall. The term Gifted refers to anyone of above average intelligence.

Twice Exceptional, 2E – 2E simply means a person is both Gifted and has some other issue, usually a learning difference such as AS (Autism Spectrum), ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), or similar.

Cademy notes: NLD is not listed in the DSM-4 book. So some schools, which may have wonderful programs for Asperger’s, refuse to help kids with NLD.

< My Thoughts > “…NLD is not listed in the DSM-4 book…”

The latest Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) may consider NLD under “Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders”, as it now includes Asperger’s in the ASD spectrum, which would also qualify that student IF they were retested under the DSM-5..

REFERENCES: UNIT 2 – Why Is It Autism? –

CHAPTER 1 – DIAGNOSIS & DSM-5

Ambersley, K. (2013). Autism: Turning on the Light: A Father Shares His Son’s Inspirational Life’s Journey through Autism; eBook Edition.

Barnes, E. (2014). Building in Circles: The Best of Autism Mom; eBook edition.

Bent, C., Barbaro, J., et al. (2016). Change in Autism Diagnoses Prior to and Following the Introduction of DSM-5; Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders; V47, p163-171.

Brignell, A., Williams, K., et al. (2015). Regression in Autism Spectrum Disorder; Journal of Pediatrics & Child Health; V51:1, p61-64.

Brodie, P. (2013). Second Hand Autism; eBook Edition.

Cademy, L. (2013). The Aspie Parent: the First Two Years, A Collection of Posts from the Aspie Parent Blog; eBook Edition.

Conti-Ramsden, G., St.Clair, et al. (2012). Developmental Trajectories of Verbal & Nonverbal Skills in Individuals with a History of Specific Language Impairment: From Childhood to Adolescence; Journal of Speech, Language & Hearing Research; V55, p1716-1735.

DSM-4 (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition; Publishers, The American Psychiatric Association (APA), Washington, DC.

DSM-5 (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition; Publishers, The American Psychiatric Association (APA), Washington, DC.

Dobbs, D. (2017). Rethinking regression in autism: The loss of abilities that besets some toddlers with autism is probably less sudden and more common than anyone thought; Retrieved online from – https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/rethinking-regression-autism/

Elsevier (2021). Childhood Disadvantage Affects Brain Connectivity; Retrieved online from Elsevier – https://neurosciencenews.com/

Fedele, R., (2018). Working Life: Tackling the Challenges of Autism; Nursing & Midwifery Journal; V25:8, p24-24.

Hayes, J. (2020). Drawing a Line in the Sand: Affect & Testimony Autism Assessment Teams in the UK; Sociology of Health & Illness; College of Medicine & Health, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK.

Healthline Staff Writer (2020). Autism: PDD-NOS; Retrieved online from – https://www.healthline.com/health/autism/pdd-nos/

Johnson, I. (2014). The Journey to Normal: Our Family’s Life with Autism; eBook Edition.

Kim, H., Keifer, C., et al. (2018). Structural Hierarchy of Autism Spectrum Disorder Symptoms: An Integrative Framework; Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry; V59:1, p30-38.

Ming, X., et al. (2011). Access to specialty care in autism spectrum disorders: a pilot study of referral source; Health Services Research; V11:99, p1-6.

Myers, S., et al. (2018). Autism Spectrum Disorder: Incidence and Time Trends Over Two Decades in a Population-Based Birth Cohort; Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders; V49, p1455-1474.

Ozonoff, S., et al. (2015). Diagnostic Stability In Young Children At-risk For Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Baby Siblings Research Consortium Study; Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry; V56:9, p988-998.

Piven, J. (2015). On the Misapplication of the Broad Autism Phenotype Questionnaire in a Study of Autism; Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders; V44, p2077-2078.

Thomas, M. & Davis, R. (2016). The Over-Pruning Hypothesis of Autism; Developmental Science; V19:2, p284-305.

Thomas, R., et al. (2016). Rates of detection of developmental problems at the 18 month well-baby visit; CHILD: Care, Health, & Development, V42:3, p382-393.

Thrive Works Staff Writer (2019). DSM-5 Assessment Coding: Autism Spectrum Disorder; Retrieved online from – https://thriveworks.com/blog/dsm-5-assessment-coding-autism-spectrum-disorder/

Thrum, A., Lord, C., et al. (2007). Predictors of Language Acquisition in Preschool Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder; Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders; V37:9.

Whiffen, L. (2009). A Child’s Journey Out of Autism: One Family’s Story of Living in Hope and Finding a Cure; eBook Edition.

Wong, M., & Heriot, S. (2007). Vicarious Futurity in Autism & Childhood Dementia; Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders; V37, p1833-1841.

Fedele (2018) feels that people who are prone to ‘restrictive repetitive’ behaviors (RRBs) have learned to cope through a wide range of behaviors; such as obsessions, ritual and insistence on sameness, and layers of other persistent manifestations.

In nursing, when I first began working with people with autism, people across the spectrum, I learned to recognize cues that they were having some sort of difficulty. They would retreat into Restrictive Repetitive Behaviors (RRBs), experiencing anxiety without the necessary therapeutic tools or training to solve the problem any other way.

Also, I learned to induce them to learn new tasks by first playing my ukulele. And, by taking a large chunk of the task, and breaking it into smaller pieces of the whole. Registered Nurses can take up the nursing challenge by learning to understand and work with the autism population. Saying that this sometimes takes years.

Barnes (2014) tells us – My name is Elizabeth and I am an Autism Mom. Our son, who we will call the Navigator, is nine and was diagnosed on the Autism Spectrum at the age of seven. Before his diagnosis, I had heard of Autism – non-verbal children who don’t like to be touched, who rocked, and who ritually lined things up. My son had none of these characteristics, so when he started having difficulties in pre-school interacting with other children, transitioning from one play area to the next, following instructions from teachers and staff, I didn’t initially think “neurological disorder.”

Then came a call from his first-grade teacher: “I am not a doctor or psychologist, but I spent 15 years in Special Education, and I think your son may have Asperger’s.” One of the American Psychiatric Association descriptions is that, “symptoms are not fully recognized until social demands exceed the child’s capacity.”

After testing by both the school and privately, he was diagnosed to be high-functioning on the Autism spectrum; Asperger’s. He receives special education services through the school.

Within a year after the diagnosis, I quit my full-time job to stay home and provide him structure and support. It was a relief to no longer feel like his behavioral issues were the result of bad parenting, or something we were doing wrong.

There is no one thing, or even series of things that work all the time, or are even discernible as a pattern. There is a need for constant analysis and creativity, which is exhausting and sometimes seemingly fruitless. Now when he melts down or perseverates I can (most of the time) calmly help him through it and not cry afterwards (most of the time).

< My Thoughts > “…need for constant analysis and creativity…”

This Barnes excerpt says so much. It tells us so candidly how Elizabeth felt that she needed to change her identity from ‘everyday’ mom to ‘Autism’ mom.

Bent, et al. (2016) believe that access to specific autism intervention and funding services are largely dependent on an exact diagnosis of ASD. Changes to the DSM-5 diagnosis criteria may therefore have a substantial impact on access to, or continuation of services. They noted that data had been ‘de-identified’ (personal information identifying ‘study participants’, between 2010 and 2015, has been electronically removed) for the 32,100 children aged under 7 years utilized in this study.

Suggesting that the more stringent DSM-5 criteria may be responsible for the seemingly ‘downtrend’ in recent diagnoses. Another reason may be the recent inclusion of – sensory interests, sensitivity, aversions, and removal of language difficulties from the core DSM-5 criteria. In all regards, the authors remind us that program eligibility criteria require the diagnose to be confirmed, exactly. The DSM-5 criteria must be designated by a pediatrician, psychiatrist, or qualified multidisciplinary team which includes a psychologist and speech pathologist. They suggest that more cases may be identified as clinicians become familiar with the new protocol, thus resulting in longer waiting time for anxious parents.

< My Thoughts > “…more cases may be identified…”

As more cases are identified, there is a need for constant analysis, creativity, and patience as a parent of a child with autism. Also, as an experienced special education teacher with a heavily increasing caseload of students with autism, this is so true. Added to that – There is no one solution or even series of solutions, or educational programs which will work every time for every child. Parents working with teachers as well as the multidisciplinary team will succeed.

Kim, et al. (2018) disclose that fundamental questions regarding the classification of the disorder remain unresolved. Added to that are the meaningful differences between parent and teacher reports regarding the child’s behavior. The need for collecting more in-depth data.

They site Initial Parent and Teacher Reports which begin by using vague descriptive words or phrases, such as –

Acting peculiar …

Doesn’t do well…

Not interested…

Unaware of…

Inappropriate response to…

Acts or reacts strangely…

Upsets easily…

Strange fascination for…

Excessive preoccupation with…

< My Thoughts > “…more in-depth data.”

In the new DSM-5, more ‘in-depth’ impairment criteria for autism classifies symptoms by also including such things as –

- Presence of symptoms in the child’s early developmental period.

- Significant impairment in important areas of functioning; social, occupational.

- NOT better explained by a specific intellectual disability.

- Has ‘severity specifiers’ as to the degrees of support each impairment requires; 1) Needs support 2) needs substantial support 3) needs very substantial support.

Thus, a clarified diagnosis could include one impairment needing Level 1 support, where a more severe impairment would require a Level 2, or Level 3 support.

Thomas, R., et al. (2016) think that most developmental problems are readily evident at the 18-month ‘well-baby’ visit. But these authors say that family physicians or pediatricians do NOT always know if the problem they’re seeing is due to the child’s environment, possibly inadequate parenting skills, or clinical screening problems.

< My Thoughts > “…developmental problems…”

Hopefully, developmental problems being seen by clinicians should be referred to a developmental specialist. Alarmingly, I have discovered that many generations of children have never experienced a scheduled ‘Well-Child’ visit by a pediatrician, but only are taken to see a doctor if they are sick. Sometimes this is due to the ‘insurance’ coverage, or lack thereof. Or, a multitude of resource, cultural, philosophical, and misinformation reasons.